Hey Cobbers,

Our regular Thursday purveyor Happyman has done the ‘Oh so Australian’ thing and chucked a sickie before the ANZAC public holiday this year, so I’ve stepped in to plug the breach on short notice. But it’s no chore as I do confess to being a little chuffed to come off the pine and share a few thoughts about ANZAC Day and how it intersects our strange game of rugby, at least for me.

To refresh all and sundry, we all know (or at least should know) that on 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and his missus, Sophie the Duchess of Hohenberg, were shot by a Bosnian Serb emo uni student named Gavrilo Princip. From there, like an old-fashioned Friday night at the pub, the protagonists grabbed their respective nationalist mates and before anyone could say “How about we just get a kebab instead?” things got way out of hand.

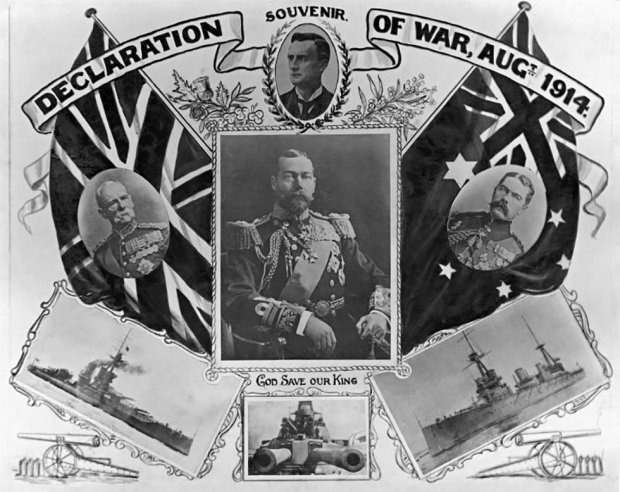

Over on our side of the world, the Australian government received a cabled warning from the Empire Foreign Office in the early hours of 30 July 1914 about the “imminent danger of war” only about 6 hours before Germany waded through Luxembourg and Belgium on its way to France. And so it was of no real surprise that on an otherwise drizzly early morning in Sydney on Wednesday, 5 August 1914, the telegraph lines chattered out that Germany and Britain (and thus we Aussies and Kiwis as dominions of the British Empire) were formally at war as of 4 August 1914.

Shortly thereafter the Australian government confirmed its alignment, with both Prime Minister Joseph Cook and Opposition Leader Andrew Fisher briefly suspending their electioneering to pledge full support of the Saxe-Coburg-Gotha Empire. With that announcement, the excitement took hold with the only real concern seeming to be that that the whole shebang might be over before any of our lads got to Europe to have their crack at the dastardly Hun.

Thus, the whole bloody disaster of the Great War began with effervescently keen Australians’ and New Zealanders’ first major deployment being the doomed push on Constantinople via the landings near Ari Burnu, on the Thracian Chersonese. That Churchillian inspired 25 April 1915 invasion of the Gallipoli peninsula, later renamed ANZAC Cove, lasted around 8 months, leaving around 11,500 ANZACs and some 87,000 Turks dead and became a formative crucible of Australian legend and identity.

On reflection, what sobers me each ANZAC Day so many years later is the realisation that from an Australia scarcely a dozen years post Federation, with a population of around 4.5 million people 420,000 Australians would enlist. Of those, 325,000 deployed overseas. Of those, 155,000 recorded wounds and 60,500 died. Likewise for the Kiwis, from a population of around 1.1 million, some 100,000 served overseas with 35,000 subsequently wounded and some 17,000 left dead.

To put it simply for both countries, just short of half their whole military-aged male population went into uniforms. And of them, just shy of 1 in every 5 men who then went overseas didn’t come back. Bloody hell.

And some 20 years later we would do it all again.

With reference to rugby, I’ve written before of the lads who played the last pre-war Tasman Test on 15 August 1914. It was the third test of the series, played at the SCG. For the record, Australia lost the Test 22-7 and New Zealand clean-swept the series 3-0. Kiwi bastards.

Of more import to this article though, of the 15 Aussies who played that day, 10 subsequently enlisted and 4 paid the heaviest price. For the ABs, they posted similar numbers with 4 of their own likewise not returning.

However, as sobering as those stats and facts are, sometimes I cannot help but feel a little disconnected from them. I mean, they were just normal men weren’t they? But for the circumstances of history, they weren’t too dissimilar from the likes of you and I. But between the enormity of the numbers, the too often elevating of their memories to seemingly archangel status, the cracked leather frames holding fading photos of fabled heroes and the surreal jerkiness from snippets of cinema footage, for me there was a distance, a disconnect, an inability to align the normality of those lads with those of us who came after. Ultimately, understandably I guess, I couldn’t connect, and so I would often ask myself “Who were those men?”.

Therefore, it was with a release of real emotion that I stumbled onto an historic pearl a few years ago, while doing some research for what was the 150th anniversary celebrations of the rugby club I’ve been associated with for some 25 years now, the Drummoyne Dirty Reds. Out of the blue, on a hunch, I found a connection between that ANZAC mystique and a nobody Joe-average clubland battler like me, I found a little nexus that gave context. And I thought to share that today.

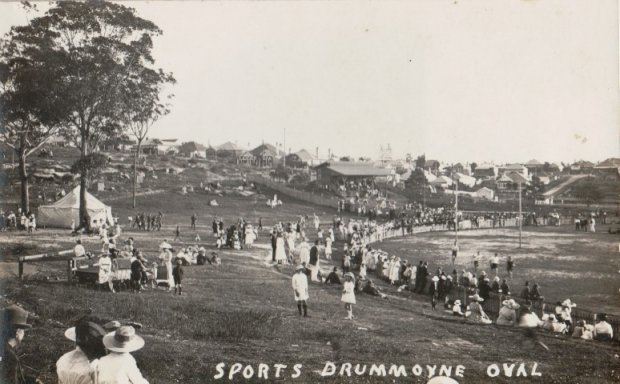

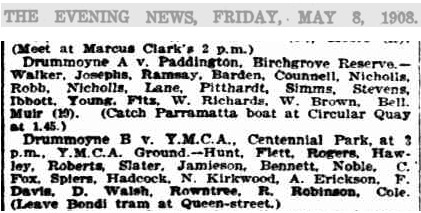

What did I find? In researching the Sydney Evening News of Friday, 8 May 1908, towards the bottom of page 8, I found lists of fixtures and teams scheduled to play in the next round of the NSW Metropolitan Rugby Union competition the day after (being Saturday). Those fixture lists generally included the grounds, kick-off times and often most helpfully, the ferry and/or bus times recommended to get there on time. But most importantly, they included the names of the players.

Among the otherwise largely amorphous mass of print, there were two matches that stood out most clearly to me: Drummoyne A v Paddington to be played at Birchgrove Reserve (recommending the Parramatta ferry from Circular Quay at 1:45pm) and Drummoyne B v YMCA at Centennial Park (best to get the Bondi tram from Queen Street for a 3pm kickoff). And among the Drummoyne B team, the dirt trackers, the tag-alongs, the guys so relatable to the never-was-so-cannot-be-a-has-been club-warriors like so many of us, one name subsequently became my link: A.Erickson.

Who was A.Erikson? With a bit of fossicking about the interwebs I discovered that A.Erickson was Albert Victor Erickson, one of four brothers (Roy, Albert, Bertie and George), the children of John and Margaret Erickson who had all attended Drummoyne Public School and in 1914 had all resided at 3 Thornley Street on the Birkenhead side of Victoria Road. All four brothers enlisted in the AIF during 1915, with Albert, a book keeper by trade, being initially assigned to 3rd Battalion of the AIF (part of 1st Brigade). After the ANZAC withdrawal he was redeployed to 45th Battalion and so to France where in August of 1916 all four brothers found themselves at the human mincer known as Pozieres. And it was on those killing fields, some 16,800km from hearth and home, where both Albert and Roy were killed alongside some 6,800 other ANZACs – Roy by shrapnel and Albert crushed in a trench collapse during heavy bombardment. Pozieres likewise saw the youngest brother George badly injured and invalided home. It appears Bertie was the only brother who survived not just Pozieres but also the war relatively physically unscathed.

Suddenly here was not just another ANZAC who had strapped on rugby boots, but had done so for my club, and further had done so in the B teams alongside the seconds, the ressies, the middle-graders. Here was a guy who had not just worn the jersey, the colours that I wear, but who had done so not as a ‘legend’, not as a Wallaby, but rather as an ordinary fellow, a simple clerk, someone who I imagine had eagerly sought the team-sheets and hoped to hear or see his name called in the higher grades just as I had so many times. Here was a connection that I felt with such clarity – the sort of 20-something lad that I charge about the paddocks with every Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday, and here was also the tragedy I could now touch so tangibly.

I find myself returning to the familiar exhortation, to that provocation that has pricked my soul so relentlessly over the years, but which is now further loaded with an affinity so real I can smell it. Now I better comprehend that long before I came to my club, there were good folk who did their bit, lived out their lives and weaved their actions into the fibre of this club, every club, my club. And they weren’t all legends and Wallabies. Many, dare I admit most of them, were just battlers and ordinary blokes like me: ressies, middle-graders, benchies. Those were the people who spun the fabric and stitched the cloth of that which I now wrap myself in. As I add my stitch to that same jersey, I’m even more aware of the legacy that I will some day hand on to those who come after.

That I’ll add my stitch to the jersey is unquestioned – by act of simply pulling the jersey over my melon that die is cast. Rather the question now becomes a matter of what sort of stitch will I leave? Will it be a stitch of honour? Of pride? Of the sort to be remembered worthy of the club? Or will it be such a stitch I would rather it were not?

On this Friday at our little local ANZAC dawn service I’ll remember Private Albert Victor Erickson, born 1892, service number 3046A, KIA at Pozieres on 6 August 1916. And on Saturday, as I once again tape up my boots and pull that now-familiar Dirty Red jersey over my head, I’ll remember him again. For if I’m to wear the same jersey as Albert Erickson, who grew up down the road, went to the local school, played for his local rugby B-team on Saturdays just like me, and was killed in action far from home, then I pray my stitch is a good stitch in the scheme of all things rugby – a stitch that in some small way is worthy to lay alongside his in the annuls of our club’s jersey.

And so, with that challenge reverberating in my conscience as the piquant stench of liniment fills my sinus and the air fairly crackles with adrenalin, I’ll link arms with my clubmates – those there and those not – and roar at both them and the universe once more:

“So what’ll it be then lads? What’s your stitch gunna be today?”

Lest we forget.