The IRB has done it again. It ignores the need to streamline a global season, despite almost all rugby stakeholders wanting one. It refuses to regulate the player drain, whereby rugby communities in the Southern Hemisphere become factories churning out product for cashed-up European clubs, who consequently have little incentive to develop local talent. And it turns a blind eye to the ever-increasing amount of rugby played each year, guaranteeing high rates of player attrition, shorter careers, and cheapened contests.

Deciding for once to trade inertia for action, the IRB has altered the one core rule underpinning international rugby eligibility requirements: that at a senior level, players who play for one country can only thereafter play for that country.

In 2013, the IRB altered its Regulation 8 governing international eligibility, so as to broaden the strength of the Sevens competition at the Rio de Janeiro Olympics. The new Regulation 8 stipulates that any player that has not played test rugby for eighteen months and qualifies for the another country via his passport can compete at the Olympic Games so long as he has played in an Olympic qualifying event (ie. a Sevens World Series competition) beforehand. The lag time will be three years, rather than eighteen months, for future Olympic Sevens events.

So far so good. The aim is clear enough: to allow Pacific Islanders who have played for New Zealand or Australia to represent their original countries at the Olympics. Few complaints; after all, the Pacific Islander rugby communities get the shaft in almost every dynamic of the international rugby market. However, the Regulation also stipulates that any player making a switch to a new country would then be prevented from playing for the original country for eighteen months thereafter. This loophole in the IRB eligibility requirements would therefore by default make that player eligible for the new country in full internationals thereafter, including at the 2015 World Cup.

Needless to say, the lawyers at the IRB should be hung out to dry. The organisation has been scrambling to cover up its massive stuff up, publicly confirming that the IRB eligibility requirements loophole won’t be closed: “The Regulation 8 exemption governing eligibility for the Rio Olympics was approved by the IRB in 2013 and applies with a stand down period of 18 months. Any player making the switch would then be tied to that country.”

Three major problems in these IRB eligibility requirements arise.

More player drain

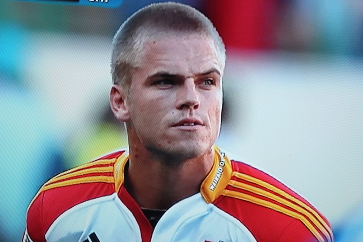

The first is that the new regime allows players who have chased the money overseas and abandoned other countries’ investment in their rugby futures to have the best of both worlds. They can return to international rugby elsewhere and on their own terms. This includes not only veterans with long international careers, like Sitiveni Sivivatu and Joe Rokocoko (both Fijian passport holders), but also guys who played only a few tests and left to chase big European contracts, like Isaia Toeava and Rudi Wulf (Samoa) and Sitaleki Timani (Tonga).

In other words, the new Regulation 8 will help further facilitate the player drain to the northern hemisphere, the biggest long-term structural problem in international rugby at the moment. Leading players will be able to have their cake and eat it too, at the cost of the integrity of international rugby and those investing in developing young players across the globe. It won’t be a good look if after a squillion tests for Australia, including two Lions tours, George Smith turns out for Tonga at the next World Cup at the expense of young local talent.

The switcheroo

The second problem is that the new Regulation 8, designed specifically for Rio, in fact makes it all too easy to use Sevens as a ruse to make switches of nationality entirely intended for international rugby. Players don’t need to make the final Sevens squad for Rio to achieve a nationality switch. All they need to do is compete at one single qualifying event.

Sita Timani is pretty unlikely to have the skillset to be chosen for the Tongan team at Rio, presuming Tonga qualifies (a big if). But in a normal 12-man Sevens squad, big Sita could run on for Tonga for a minute or two in a dead rubber match in a preceding qualifying tournament and then turn out for them at the 2015 World Cup. Such a situation would be little short of a farce, with Timani having turned his back on a Wallaby career barely two years before.

Inconsistency

The third problem in these IRB eligibility requirements is the lack of consistency. The IRB’s current rules on international qualification require only three years residency in a foreign country or a grandparent from that country. You don’t have to hold that country’s passport to play. Players like Antonie Claassen and Bernard Le Roux, both South Africans, have turned out for France simply because they play their club rugby there and have not previously played for South Africa. Gareth Anscombe has just last week decided to head over to Wales, where ancestry gives him qualification for the Welsh.

Now, however, a passport has become the standard for qualification for test rugby for some players (like Sivivatu) and not for others (like Claassen). It shouldn’t be too hard to insist that one rule applies to everyone, yet the IRB is right now taking apart the only rule that does apply to everyone equally: the stipulation that once you play senior rugby for one country, you can only play for that country.

The IRB needs to start over. It needs to host all the stakeholders and sort out a regime for the business of rugby that actually displays some vision: a regime that will be applicable in ten, fifteen, twenty years’ time. Not just an ad hoc regulation for the next Olympics, scrappily drafted and full of problems, but a new approach that ties each of rugby’s various issues together into a coherent whole.

What are your suggestions for better eligibility requirements?