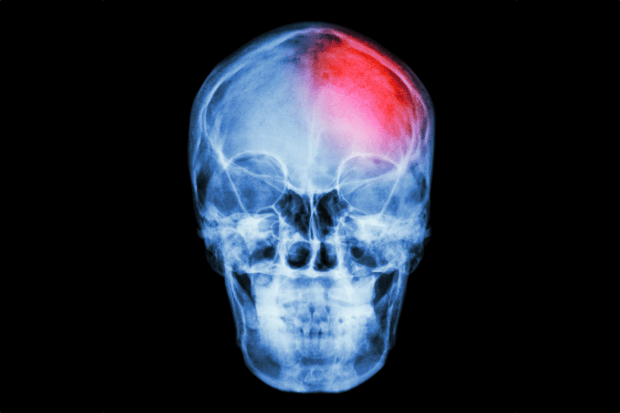

Research published today shows that the longer you play(ed) rugby, the higher your risk of developing CTE.

This paper from the University of Glasgow, University of Sydney, Boston University and a host of associated hospitals, looked at brains donated to science where rugby was the primary sports exposure in brain banks in Glasgow, Sydney and Boston. They found 31 such brains in total, and 21 of the brains showed signs of CTE. Most of these brains with CTE (13) were from people who had only played at an amateur level.

Central Findings

Of the 21 with CTE, 14 had low-stage pathology, 7 had high-stage. This is a bit hard to put simply, because it’s based on a post-mortem analysis of changes in a specific in neurofibrillary tangles to a stain called p-tau. However, there’s a loose correlation that if the brain post mortem has low-stage pathology the person showed no or little clinical signs while alive. High-stage pathology is linked to more common appearance of severe clinical signs. These included memory loss, aggression, personality changes and the like. All the things you see in interviews of players with CTE, and read about.

Where they could find a position, the players were evenly split between forwards and backs. The time that they played ranged from 2-35 years. The age at death varied from 17-95. If they allowed for changes to the brain based on age at death, there were basically no differences observed except a time-of-play link to prevalence of CTE. The longer you played, the more likely you were to show symptoms.

It’s Not The Concussions that Matter

Note that, 19 of 29 (2 unknown) reported a history of traumatic brain injury (TBI) – that’s loss of consciousness and/or a history of concussion. There was NO statistical difference in the development of CTE in this group, to those that had no history of TBI. The authors suggest that exposure to repetitive head impact over time is the driving force here. This mirrors findings with other contact sports where players with longer careers have higher prevalences of CTE.

As a side note, this may suggest why we had a sudden spike after the sport turned professional. Although this study highlights that amateurs are at risk too, elite amateurs turning professional went from contact training a couple of nights a week, plus playing (they obviously did fitness training and the like as well, probably on all the other days) to contact training loosely every day. That changed rapidly as people understood how to train better, prepare for matches better, even before the CTE crisis exploded, which might help explain why the number of new cases seems to be decreasing, even before changes to high tackle laws and the like were introduced.

Things To Bear In Mind

There are issues with this study. It’s a volunteer study on brains donated and then available to be examined. It’s always important to consider why are these people donating their brains in this way? Are they people who consider they might have CTE, they’ve shown symptoms in the case of the younger deaths, and dementia that may or may not be CTE in the older deaths? It’s impossible to be sure. However, that would merely dilute the prevalence, we would go down from 2/3 of those examined being affected to some lower proportion of former players actually being affected. The dosing effect would be lower, the amount each year you play increases your risk, but the shape of the findings would remain.

Takeaways

- Playing rugby is risky

- The longer you play, the more at risk you are.

- It’s an issue in the amateur game as well as the elite game

- Getting concussed isn’t the be-all and end-all, repetitive sub-concussive head injuries are just as bad.