Most aspects of rugby are better now than back in the day — except for scrums. From being a jewel in our crown they’ve become a millstone around our neck, and a new study run by the IRB itself has now proved them an unnecessarily dangerous one at that.

Scrums are collapsing, the number of resets is multiplying; front-rowers’ necks and backs are hurting; referees are guessing; dominant scrums are wondering, early engages are increasing, scrum tunnels are disappearing, scrum-halves are cheating; old skills are dying, time wasted is rising, and fans are leaving because value for money is decreasing.

Case study: Ireland v. Australia RWC 2011

There were 22 scrums in this pool game refereed by Bryce Lawrence, with 11 collapses and seven penalties. 43 per cent of the game’s points came from scrummage offences and it would have been more than half if the kickers had been successful with all their attempts.

What happened to the scrum?

A new thing happened: the power hit. It was never part of the game, but it snuck into it.

Back in the day, packs used to walk in together passively, front row first, then showed their power and technique on the power shove after the others were attached and the ball was put into the scrum. In the late 1970s some coaches got their packs to lurch into the other scrum with a bit of force. The lurch gradually became a hit, but it wasn’t too harmful.

As Ewen McKenzie said a few years ago:

I cast my mind back 20-odd years and even looked at some video. We actually used to morph the scrums together. The front rows joined even before the second rows had arrived.

But when the players were paid to be in the gym in the professional era, this walk-in engagement became a hit, and then a power hit.

The scrum contest became a hit contest: a sprint across a short distance with two 900-kilogram packs colliding — and because they couldn’t scrum head-to-head there was often a natural, sudden clockwise wheel. There was also a natural hinging down or standing up, unless the vertical forces met just so.

Things would not have been so bad if every loosehead prop could get a grip with a long bind on his tighthead opponent, but the tight 1970s disco tops of the players didn’t allow it. All Black Ben Franks said that they made it difficult for the forwards to bind:

Especially for a loosehead, it’s a lot harder to get that initial bind — there’s nothing really to grab so you’re kind of grabbing for skin!

What’s being done?

Some new research looks interesting.

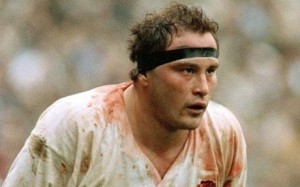

Brian Moore, a solicitor and ex-England hooker, is a long-time critic of the power hit and has commented recently in the Telegraph on many of the above matters here. In the article he mentions:

…the IRB published a report on the most detailed examination ever of the scrum, undertaken over three years in South Africa and at Bath University. It isn’t revolutionary in the sense that it contains startling results, indeed it mostly confirmed many things already known by experienced practitioners.

The point is, that for the first time these things cannot be dismissed as anecdotal or personal. They come from tests carried out at six levels of rugby, from schools to international.

The research recommends, amongst other things, the removal of the ‘artificial hit’.

Moore gives a warning:

The IRB, particularly its refereeing department, is now in an entirely new legal position. Previously courts had to decide between the opinions of opposing expert witness, of which I am one, based on their personal experience and knowledge. Now they have concrete research and recommendations from rugby’s global governing body to assist their decision.

The IRB, RFU and other Unions can no longer defend cases by claiming a contrary view is just one expert’s opinion. If they do not take all reasonably practical steps to follow their own safety recommendations they will have no defence, legally or morally.

In a conversation between Moore and Brett Gosper, CEO of the IRB, on Twitter the other day Gosper said to Moore:

http://twitter.com/brettgosper/statuses/260830318616002560

The IRB should have read the signs better at the end of the 1990s. The power hit, already born, but young, grew to be the monster it is now, and instead of snuffing the life out of it lawmakers tried to control it. They still are, without success.

I say: ‘Crouch — Aim — Fire’.

Kill it; kill it now.