In an earlier article, I talked about how Australian rugby traditionalism had kept the Wallabies running a playmaker in the 12 jersey while the other dominant rugby nations have all switched to crash ball runners. Even the Australian Super Rugby franchises have made the switch, preferring to select players like Samu Kerevi, Karmichael Hunt, Irae Simone, and Lalakai Foketi. With Kerevi’s form this year as well as Beale’s form at fullback it will be hard for Michael Cheika to justify the continuation of this policy during the World Cup.

Another area in which Australian rugby is still playing last year’s game is off the back of the lineout. In the traditional view, the All Blacks are experts at first phase tries – partially as a result of Australia’s impressive late ‘90s defensive structure, which was impossible to break once established. However, in the last couple of years we have seen a drastic decrease in the number of tries scored by the All Blacks from a set piece. I was unable to find any clear statistics on this, but they had scored only three set piece tries in 2018 at the halfway point in the Rugby Championship. The All Blacks had scored 37 tries in total by this point of the year. One of these was essentially created by referee obstruction, and if we exclude this we can see that only two from 36 legitimate All Black tries in their first 6 games last year came from a set piece.

One of the reasons for this can be found in the rulebook. Law 18.13 states that “the team throwing in determines the maximum number of players that each team may have in the lineout.” The only restriction is that there must be at least two players in the lineout in addition to the thrower. This gives the attacking team the ability to ensure that there are no forwards in the defending team’s backline by choosing a 7-man lineout. Some canny teams will prefer to put their scrumhalf into the lineout to free up a loose forward to defend in the flyhalf’s channel, but this can be avoided by simply choosing an 8-man lineout on subsequent occasions. This ensures that the backline is spread thin to remove the possibility of a gang tackle, and also removes most of the larger players from the picture.

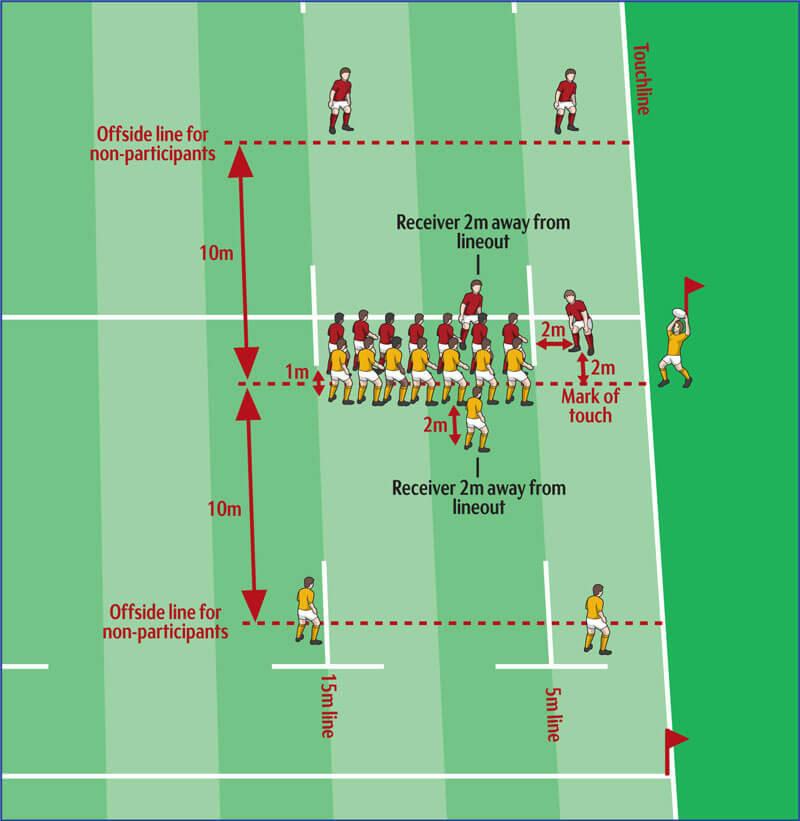

The second reason is also found in the rulebook. Law 18.35 states that “players not participating in the lineout must remain at least 10 metres from the mark of touch on their own team’s side or behind the goal line if this is nearer.” In the case of the goal line being nearer, a driving maul may be preferred tactically. Otherwise, when an attacking team is receiving the ball off the back of a lineout, there is a vast 20 metre gap between the first receiver and the defending team (pictured in the World Rugby image below). Considering that the gap between teams in general play is usually between a few feet and nothing (the length of the ruck), the lineout creates an invaluable opportunity to get a charge-up.

These two rules combine to create a superpowered opportunity: not only does the attacking player get a 10-20m charge-up before contact (depending on the speed of the rush defence), by choosing a larger lineout they can do so free from fear of being hit hard in contact by the opposing forwards or by multiple defenders at once. Having a scrumhalf with a solid long pass introduces the ability to select a weak defender to run at as well, by allowing the ball to reach the receiver further along the backline. Some teams will also throw the initial pass to the flyhalf before giving the ball to the crash ball runner.

This is why Sonny Bill Williams is still the best option for the All Blacks at 12 if he is fit. Ngani Laumape and Ma’a Nonu (who are still primarily crash ball runners rather than playmakers) have made good cases for selection, but having a crash ball runner with a strong offload ability means that even if the first defender makes the tackle, there will still be a hole for the support player to run through – and the support player will also have had a charge-up of their own. However, the only mandatory selection criteria for the original runner is that they should be difficult to tackle. Preferably, they should be both big and fast, but the ability to run a good line or wrongfoot defenders are high prized as well. This is also why Kerevi is the best option for the Wallabies at inside centre, why Hunt is probably his best replacement, and why a playmaker shouldn’t be selected in the 12 jersey in the current rugby metagame.

Even in an instance that the tackle is successfully made without an offload, usually there is a solid territorial gain from where the lineout occurred and the ball is usually recycled quickly due to the forward momentum, pre-selection of support runners who can clean out effectively, and the fact that the defending forwards are still tied up at the lineout. This means that the second phase will usually also yield good results on attack, because the second-best crash ball runner (usually the blind winger) can receive the ball quickly while the defence is still backpedalling and before the forwards have reached the far side of the field. This creates a similar set-up to the first phase, with the difference being that the defending team is closer, but this is offset by the fact that they should be going backwards which is almost preferable.

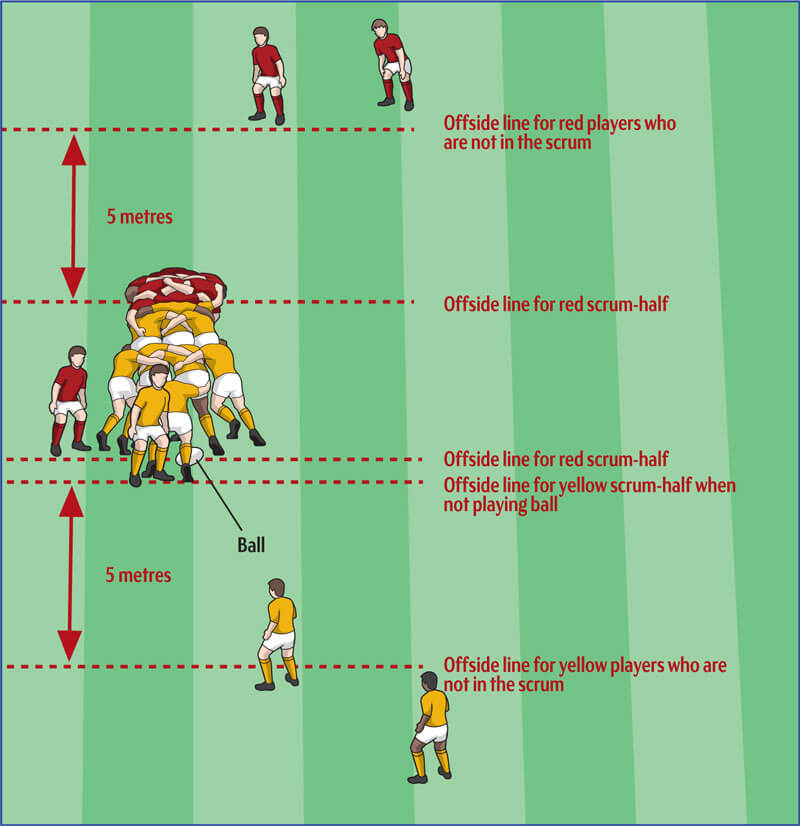

At this stage, the attacking team has gained a lot of ground and put the defenders on the back foot. They have also created good opportunities for linebreaking runs and offloads. Only one pass per phase was required, on both occasions from a specialist passer (the halfback), and the possibility of losing the ball at the ruck is minimal because the attacking team knows what the play is and can set the positions and abilities of the support runners. This setup creates a good platform for a team to exit from their own 22-metre zone. It works almost as well off the back of a scrum, and though the offside line is only 5 metres (pictured in the World Rugby image below), this can be compensated for if the attacking scrum goes forward and causes the defending players to backpedal. The bigger issue is that it’s more difficult for the scrumhalf to get the ball directly to the inside centre, but this is usually resolved with a simple 8-9 play off the back of the scrum or a more classic 9-10-12 sequence.

The more traditional Australian move off the back of a lineout or scrum is to keep the ball in play for longer and utilise the dual playmaker system to put doubt into the defenders’ minds. The other backs are usually running pre-determined lines either to confuse defenders or to create a genuine option for the first and second five-eighths. The fact is that defences have radically improved in the last few years and in a situation where all players are marked up defensively (such as from a set piece), it is rare to get past the defensive line. If this does occur, it is a result of a missed tackle or an offload to a support runner.

The more traditional Australian move off the back of a lineout or scrum is to keep the ball in play for longer and utilise the dual playmaker system to put doubt into the defenders’ minds. The other backs are usually running pre-determined lines either to confuse defenders or to create a genuine option for the first and second five-eighths. The fact is that defences have radically improved in the last few years and in a situation where all players are marked up defensively (such as from a set piece), it is rare to get past the defensive line. If this does occur, it is a result of a missed tackle or an offload to a support runner.

Starting with a crash ball runner targeting a weak defender is more likely to create one of these outcomes, and if the defensive line does hold then the crash ball runner puts you in a better attacking position. This is because the complex set plays tend to shovel the ball laterally, reducing the territorial gain and increasing the likelihood of a link player being tackled behind the gain line with no ruck support. These moves also introduce a lot of risk simply by including more passes and moving pieces. The inside centre crash ball is very easy to teach 30 players drawn from four different franchises in a short time, and this is why a similar style of play has been termed “Gatlandball” – because it is the go-to move of the British and Irish Lions coach when tasked with drawing players from four different countries. Gatlandball has the added connotation of attempting to draw in two tacklers on purpose in order to create an overlap out wide, which is a reasonable variation of this strategy when one is confident that the crash ball runner will still make metres and recycle quickly.

The Wallabies have been proponents of long, lateral plays off the back of lineouts and scrums for many years now. This was necessary at a time in the mid-2000s when the lineout was the only source of ball the forward pack was likely to win and the backline was potentially the best in the world. These moves should now be confined to set pieces on the opposing team’s 5 metre line, where the offside line is closer and the ball is likely to be mauled first. Across the other 95 metres of the field, utilising the rare opportunity to get go quickly recycled ball from across the advantage line with no opposing forwards in sight is a must. And as a consequence of this, having at least two crash ball runners – one of whom should be wearing 12 – is also a necessity.