In part one of this article I looked at some of the horizontal angles involved in scrums, the importance of body shape / height and how those points are relevant for the Wallabies scrum against the Lions.

With apologies in advance to Nutta, who was adamant in comments on part one of this article that I had to stop revealing secrets, I’ve got some more secrets to share today.

In part two I’m going to look at some of the vertical angles involved in scrums and how those vertical angles impacted on the clash between Ben Alexander and Mako Vunipola in the second test.

I’ll post part three of the article on Friday looking at why the flankers are so important to props and what the trial laws being introduced next season will mean for scrums.

Vertical Angles

As I showed in part one, the loosehead effectively ‘dives’ under the tighthead as they engage and then drives forward and up to disrupt the tighthead. It’s not an easy manoeuvre and only experienced looseheads are capable of doing it well.

In order for the tactic to work the loosehead has to get the back of their head under the tighthead’s chest. Due to the offset of the front rows the loosehead lines up with their head opposite the tighthead’s right shoulder and if the loosehead packs straight forward the back of their head ends up under the tighthead’s right shoulder as shown below.

With their head in this position as the loosehead lifts up their head can slip outside the tighthead’s body which leaves them with nothing to push on and they can’t transfer any force through to the tighthead.

Alternatively if the loosehead’s head stays under the tighthead’s right shoulder their upward movement rolls the tighthead in towards the middle of the scrum rather than up. We saw Alexander being rolled up and in by Vunipola in the second test but I’ll go into more detail about what was happening in those scrums shortly.

If either of these things happen there is a good chance the referee will take the view that the loosehead is pushing illegally and penalise them.

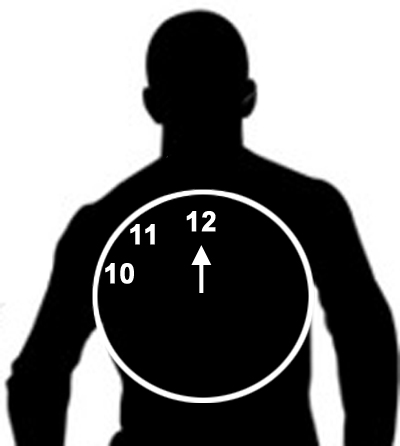

Ideally the loosehead wants to get the back of their head under the sternum of the tighthead so that as the loosehead lifts up they have something solid to drive on. A good way to think about where a loosehead engages under the tighthead is to imagine a clock face on the tighthead’s chest looking from where the loosehead is standing opposite.

The best looseheads will move the back of their head under the tighthead to the 12 o’clock position right on the sternum. A loosehead with reasonable technique will get the back of their head under the breast of the tighthead in the 11 o’clock position. A loosehead with poor technique will settle for getting the back of their head under the armpit of the tighthead in the 10 o’clock position.

There are two keys to being able to move from the 10 o’clock position to the 12 o’clock position.

- Body shape / height – if the loosehead is flexible in their hips they can get into a good low starting position to get their head down low enough as they engage. If the loosehead starts too high it’s nearly impossible to physically get down low enough to get that far under the tighthead’s chest. This is why loosehead’s are normally the shorter of your two props. There’s a reason why someone like Wyatt Crockett struggles to get under tightheads and is often penalised for angling down and going to straight to ground in an attempt to do so.

- Strength – the further down you ‘dive’ the further you have to come back up and that relies not just on getting a good strong bind but having a very strong core to lift your own body weight back up together with the weight of the tighthead driving down on top of you.

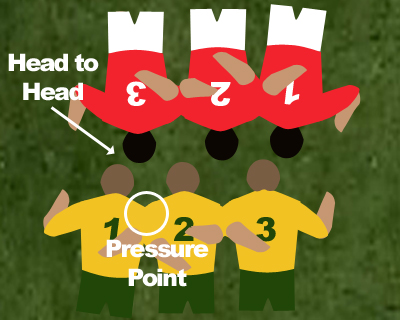

As I mentioned earlier, if the loosehead engages straight forward from their setup position the back of their head will end up somewhere between the 10 o’clock and 11 o’clock positions. To get across to the 11 o’clock or 12 o’clock positions and therefore be more effective with their drive looseheads normally setup angled in as shown below.

This means the loosehead drives in on angle, which is of course illegal. However, this tactic is used by all top level teams and referees don’t penalise it (maybe because they don’t know what the loosehead is up to).

The use of overhead cameras reveals a lot about what happens in scrums and I’ve included some examples in the video below – here’s a screen grab from an overhead clip in the RWC 2011 match between the Wallabies and Wales.

The loosehead sets up this angle by bringing their shoulder in behind their hooker’s shoulder as they bind. This bind between the loosehead and the hooker is the pressure point the tighthead aims for as he engages and drives forward. As well as getting the loosehead into position to angle in this binding tactic makes it much harder for the tighthead to break their bind apart.

It also reduces the space for the tighthead to put their head into which creates the head to head arguments you see between looseheads and tightheads as they get ready to engage. You’ll often see referees pull scrums up before they engage to sort this head to head issue out.

Let’s be clear – it is the loosehead that causes this issue by angling in and the clip I’ve included of Benn Robinson in the video below shows how the tighthead and loosehead end up disputing the space – the tighthead wants the loosehead to move their head out whilst the loosehead wants the tighthead to move their head in.

On page 2 I’ll look at the performances Alexander and Vunipola in the second test together with tactics for the third test.

We are a fan run website, we appreciate your support.

💬 Have you got a news article suggestion? Submit a story and have your say

👀 Follow us on Facebook, Instagram and X.com

🎵 Listen to our Podcasts on Spotify and iTunes

🎥 Watch our Podcasts on YouTube