The third contender for the Wallaby No. 10 jersey is a guy many could not pick out of a line-up. But astute followers of the game, fantasy rugby players, and insiders all know who we’re talking about: the Waratahs’ Bernard Foley.

Foley takes centre stage in this final instalment of the three-part assessment of the various options Australia have at flyhalf, otherwise known as the “Goldilocks” equation.

Foley takes centre stage in this final instalment of the three-part assessment of the various options Australia have at flyhalf, otherwise known as the “Goldilocks” equation.

Matt Toomua offers a lot, but might not have the ability and variety to unlock good defences.Quade Cooper lies at the other end of the spectrum, while bringing a lot of baggage and shortcomings in contact with him.

But Bernard Foley might be just right, offering something approaching the best of both worlds.

Foley was often used at fullback last year; this year he stepped into the Waratahs’ No. 10 jersey on a full-time basis and made it his own. It is worth remembering how much difficulty players have traditionally had playing five-eighth in the high-pressure Waratahs environment.

Lachlan McKay, Manny Edmonds, Duncan McRae, Shaun Berne, Christian Warner – all came to the Waratahs amid high expectations but signally failed to enjoy stellar Wallabies careers. The meat pie and Cab Sav crowd from Sydney’s northern and eastern suburbs are notoriously hard to please, but Foley has done it.

This year, the Waratahs fitfully embarked upon a new and expansive style of rugby. Coach Michael Cheika’s basic pattern to achieve momentum involved big forward runners hitting the ball up, often outside Foley.

In stark contrast to the Brumbies or Deans’ Wallabies, who largely attack the 9-10 channel off the scrum half, the Waratahs frequently sought to weaken the opposition defences much, much wider.

Only one per cent of Waratah possession – by far the lowest of any team – was dedicated to pick-and-drives. In short, the team sought to keep the ball and use it: the Waratahs kept the ball on average for 3.56 phases, the longest for any Super Rugby team.

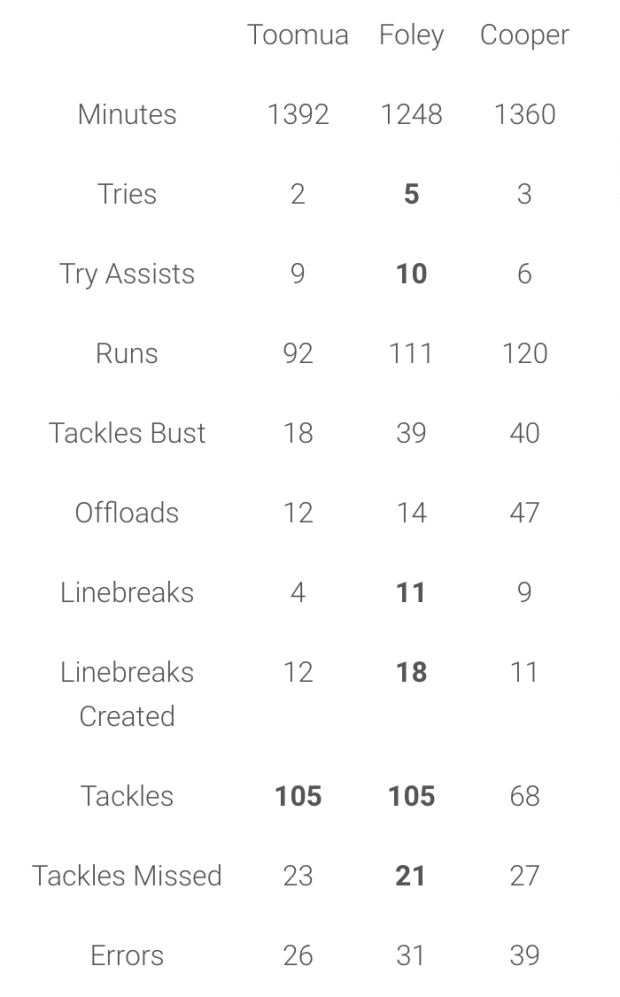

Foley was at the core of almost everything the Waratahs did well this year. The flyhalf statistics below tell a clear story; I’ve highlighted all the categories in which Foley leads the way among the three contenders.

The only category in which Foley is the last of the three is in minutes played. Foley also created more linebreaks and executed more try assists than any other player in Super Rugby this year. No mean feat.

What is even more remarkable about these numbers is that they were recorded in a team that was ultimately a genuine mid-table outfit. The Tahs won eight and lost eight. They had a slow start to the season and struggled to adapt to Cheika’s new style.

This accounted for losses of momentum, dropped balls, the odd tight loss, and the overall feeling that the team was one in transition and developing rather than challenging for the title. Yet Foley still produced the goods. In a Reds team encountering a similar stop-start pattern in their season, Cooper did not.

Foley understands space and how to exploit it; shown by the high numbers of linebreaks created and try assists. But he also offers two extra skills derived from his days as captain of Australia’s Sevens team: he provides a genuine running threat, able to take on the line, step, and accelerate.

He also has a great understanding of support play, both when looking for teammates and when supporting others, as shown in this mashup by Vinnie Goro:

His setting up of a try against the Blues shows both instincts at work. At 0:27 into the video, Foley takes the ball to the line and speeds through the gap. Almost every player in this situation would look outside for support, to speedy outside backs.

Foley instead realises that Folau is too close to him and that the better play is to step inside, commit defenders, and look for Matt Lucas running a great support line on the inside instead (not coincidentally, Lucas is also a regular with the national Sevens team). Lucas then finds Folau and the try is scored.

What I especially like here is that Foley looks for the simple but effective option. It is easy to imagine Quade Cooper, in the same position, trying something flairtastic, but ineffective – like a flick offload to Folau, or a wide pass to the right winger so far behind the play he is out of shot, or a trick grubber behind the fullback. All low percentage plays.

Another good example of what Foley brings to the table comes from this clip against the Bulls in Pretoria, which records a solid two and a half minutes of unbroken, lung-busting play at altitude (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ko-ssTQLmTw). Foley pops up everywhere.

Note his offload at 0:22 to launch the original attack, his hitting a ruck and sealing the ball at 0:38, his chase back in defense after a turnover at 1:00, forcing the Bulls runner out wide, his textbook tackle at fullback at 1:44 (and, again, imagine Cooper in the exact same circumstance) and then his backing up of the break to score at 2:22.

Watching both clips, what is particularly striking is how little Foley seems to be doing. But that’s his strength. Much like Toomua, Foley doesn’t need to do the ridiculously flashy. Instead, he underplays his hand, fits into a team structure, and the statistics are testament to the effectiveness of his impact on the team’s overall performance.

On the other hand, like Cooper, Foley can open up a defence, though often with his running game rather than high-risk plays.

His try against the Hurricanes looked just like Quade playing against some porous defence back in 2011, ball in two hands, stepping, baffling the would-be tacklers (at 1:05 in the video above). It’s the sort of try that gets better every time you watch it.

Certainly, Foley is far from the complete package. He doesn’t have a developed wide passing game (unlike Cooper – Ed.). His kicking game isn’t as good as the others’ (though the often misleading kick metres metric suggests it is, with Foley at 39 metres per kick, Toomua at 40, and Cooper at 37).

He doesn’t yet have the aura of a guy who can lead an international team around the park; Cheika often went to Berrick Barnes in the last fifteen minutes of a match to close it out.

And he makes mistakes, as the error tally suggests (though, to be fair, Brendan McKibbin’s service from the base of the ruck was often variable). However, if he has a bad day, the whole team can still function. If Cooper has a bad day, everything collapses.

This might mean Foley needs more development at Super Rugby level and a supporting role on Wallaby end-of-year tours. Or it may mean that the smart choice for McKenzie is to develop Foley promptly based as much on what he will be in a year or two years’ time, not what he is right now.

Ewen McKenzie would be a very brave man to allow his entire career to depend on the vagaries and inconsistencies of Quade Cooper, but he is all but certain to give Cooper the first shot at making the jersey his own.

However, if we use a granular approach and look at what the various options are actually doing on the field, not at what we think they are doing from overall impressions of the matches, I think it becomes clear that Foley and Toomua are the stand-out choices.