In matches involving the Wallabies over 40% of the times a team starts in possession that possession starts with a scrum or lineout (scrums 17% and lineouts 26%).

With a little over a quarter of possession coming from lineouts this is an area that requires a lot of attention – both in attack and defence. Selections must give a team the best chance of competing in the lineout, lineout strategy must be finely tuned and sufficient practice time must be dedicated to this area.

Selections must include a sufficient number of ‘genuine jumping options’ but the question is how many are sufficient? I found this topic a little hard to explain without going into a fair bit of detail – hopefully the amount of detail doesn’t cause you to lose interest halfway through before you get to my conclusions.

Throughout the article I refer to jumpers and by that I mean ‘genuine jumping options’. In international rugby, regardless of the skill of a jumper, that means being able to compete with jumpers that on average are around two metres tall. I’ve seen people suggest that an alternative way to look at this is to have a shorter player, typically a number seven, lifted by a taller lifter, such as a lock who may not be as good at jumping as the shorter player.

The taller lifter in any pod is best suited to be the rear lifter as they lift under the backside of the jumper whereas the front lifter can lift on the thigh of the jumper but no lower than that (law 19.10 (d)). In international rugby front lifters already lift as low on the thigh as they are allowed therefore any extra height from the rear lifter will not be of any advantage unless the front lifter is also replaced by a taller player which would mean removing two of your tall players as jumping options to act as lifters.

Of course other players who are not a ‘genuine jumping options’ may be used to jump in the lineout but for the purposes of this article I’ll refer to them as backups.

International teams usually include four jumpers in their pack – the two locks, the number six and the number eight. This leaves the number seven on the ground and in a better position to cover any overthrows or immediately move out of the lineout to follow the ball (whether it is won or lost).

But is it really necessary to have four jumpers? To answer that I’ll start by looking at the number of jumpers required to defend lineouts before considering attacking options.

You’d expect that defending a ‘full’ lineout involving seven forwards in the line would require more jumpers than shorter lineouts but that is dependent on whether the defending team uses floating pods or fixed pods (or a combination of both).

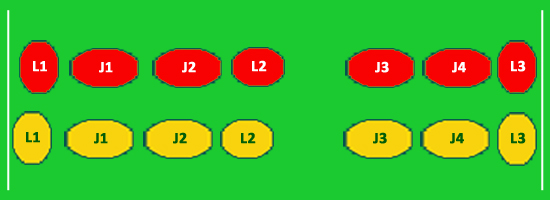

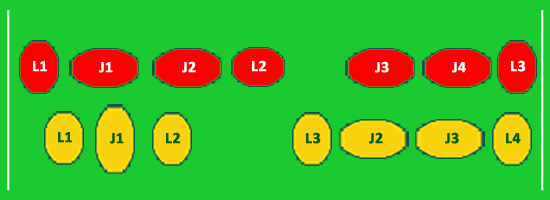

With a floating pod system jumpers / lifters match up with opposition jumpers / lifters and players try to read who will get the ball and react to lift the appropriate jumper as shown in the diagram of a typical full lineout structure below. The various players move from one pod to another dependant on where the opposition throw the ball. This system relies on all of the players being quick enough to react to the opposition as they move to jump.

If the red team are throwing to this lineout they have four options even without considering movement – throw to J1 with L1 and J2 as lifters, throw to J2 with J1 and L2 as lifters, throw to J3 with L2 and J4 as lifters and throw to J4 with J3 and L3 as lifters. As all of the players (except the end players) are facing the centre of the lineout and can therefore turn either way, there is doubt in the defenders minds as to where the ball will be thrown to.

Obviously by mirroring the setup in the lineout the defence is in position to match jumper for jumper and lifter for lifter and therefore can cover all four options. To do this would require the defending team to also have four jumpers.

Winning the lineout is often achieved just by getting into the air faster than the defenders and therefore winning the race in the air to reach the ball first – the difference between winning and losing the race can often be a tenth of a second. With the red team throwing the ball they have an advantage as they know when the ball will be thrown and should be able to react slightly ahead of the defence. If the red team throws to J2 it’s likely they will get J1 and L2 into place as lifters first and any slight hesitation from J1, J2 or L2 in the defending team to react will probably put them too far behind to even get up and compete for the ball.

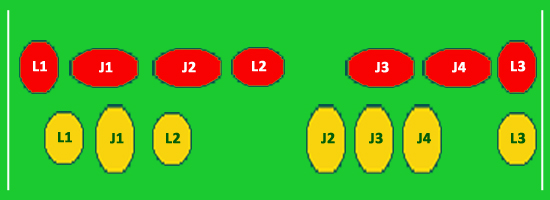

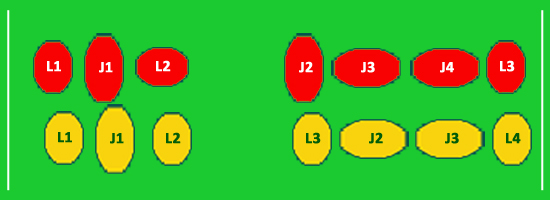

An alternative way of defending a lineout is to defend with a fixed pod system where jumpers and lifters stay within a dedicated pod that will try to move forward or back across the ground to cover where the ball is thrown to – the whole pod moves together rather than players moving from one pod to form another. The advantage is that there is less chance for confusion or hesitation between the players and therefore they should be able to lift or jump faster. The disadvantage is that the pod takes time to move across the ground to cover all the options the opposition has.

In the example above L1, J1 and L2 form a dedicated pod that will move forwards or backwards dependant on whether the ball is thrown to J1 or J2. J2, J3 and J4 form a pod with J3 dedicated as the jumper and will move dependent on whether J3 or J4 are thrown to. As they are not moving between pods all players start in position to lift, rather than facing the opposition which saves some additional time by not having to turn. L3 (who would normally be your most mobile backrower) doesn’t have a role other than covering overthrows or chasing the ball once it leaves the lineout.

This strategy reduces the number of genuine jumpers required to two (J1 and J3 in the example above) and can also be used for six man lineouts.

Some teams will choose to defend seven man lineouts with only six players allowing one forward to defend in mid-field to assist the backs. The fixed pod system can be used if this tactic is adopted with L3 dropping out of the lineout and the eighth forward acting as halfback to cover running options at the back of the lineout.

If a team is defending a four man lineout all four players in the attacking team could be jumpers but only players jumping in the middle two positions are options as they need lifters so again only two jumpers would be required in defence.

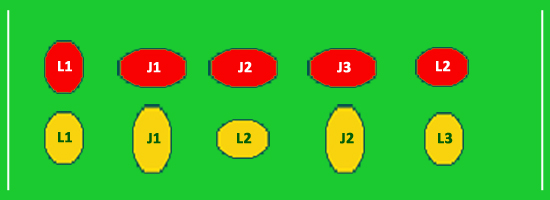

Defending five man lineouts is not as easy with only two jumpers. A typical five man ‘spread’ lineout shown in the diagram below involves three jumpers in the middle who are all options to be thrown to – if the red team is throwing to J1, L1 and J2 become lifters, with J2 as the jumper J1 and J3 are the lifters and if J3 is the jumper J2 and L2 are the lifters.

With the red team throwing to the lineout L2 on the gold team would move to either J1 or J2 in the same lifting role as J2 on the red team. However if the red team throw straight to J2 that cannot be defended using this structure as it would take too long to move either J1 or J2 on the gold team and the lifters into position to defend.

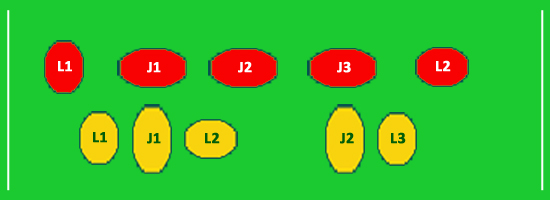

A possible alternative is to defend with two fixed pods with a single lifter in the rear pod as shown below but this compromises both jumpers ability to defend as it’s very hard for J1 on the gold team to move back to cover a throw to J2 on the red team and J2 on the gold team will have difficulty competing against a throw to J3 on the red team with only a single lifter.

Therefore a team must have at least three jumpers to be able to adequately defend five man lineouts. Given that most teams use five man options an international team must start with at least three genuine jumping options.

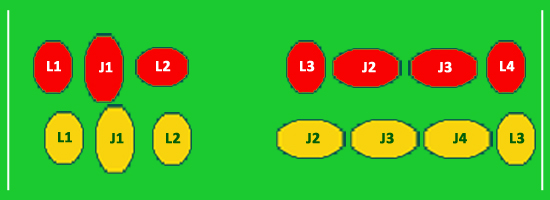

Having three jumpers also allows a team to use a combination of fixed and floating pods to defend a full lineout as shown below which increases flexibility to cover the opposition, even if they have four jumpers. A fixed pod at the front of the lineout will have to defend a throw to either J1 or J2 by moving across the ground and the floating pod at the rear will have to defend throws to J3 or J4 with the jumper and lifters being flexible. Of course the floating pod could be moved to the front and the fixed pod to the rear dependent on preferences.

In attack the only time more than three jumpers may be useful is when a full lineout is used.

There are three main reasons teams use full lineouts in attack – to provide as many options as possible to throw to; as most teams match numbers, to get the opposition forwards out of mid-field and therefore provide more space for their own backline to attack on first phase; and to provide more numbers ready to drive the ball forward rather than release it to the backline.

If a team chooses to focus on shorter lineouts they forego the opportunity to give their backline space on first phase. Instead they will position forwards in mid-field and use them to punch the ball over the gain line to get the team moving forward to start a possession sequence.

In a full lineout if the attacking team only has three jumpers and the attacking team has four, the advantage to the defending team is limited when there is little movement within the attacking lineout. In the example below if the gold team is throwing the ball into the lineout there is no advantage for the red team in having the extra jumper (J2 red matched against L3 gold) as the ball is not going to be thrown to L2 or L3.

If however movement is used within the lineout by the gold team with for example J2 gold stepping around L3 gold to be lifted by L2 and L3, then the red team would benefit by having J2 in position to move forward and be lifted by L2 and J3.

If the attacking team has four jumpers and the defending team has only three, the attacking team does have a significant advantage. In the example below with gold being the attacking team a throw to J2 moving forward with L2 and J3 as lifters is really hard for the red team to defend as their closest players are both lifters (L2 and L3).

An international team therefore needs a minimum of three jumpers and if playing a team that has four jumpers they need to make their selections based on matching that number of jumpers or at least have a fourth player who is a backup option.

In the past the Wallabies have experimented with playing two open side flankers in the same starting side (Smith and Waugh) and there are many who believe that with Michael Hooper’s exceptional form in 2012 that the Wallabies should again try that option with David Pocock starting at number six and Hooper starting at number seven.

Whether that combination would be balanced from the perspective of general play is something that is a topic of its own. Pocock has been used as a jumper by the Wallabies in the past but I don’t believe he’s one of the genuine jumping options required – whilst his jumping looks technically sound his height makes it very hard for him to compete with most international jumpers so I believe he is only a backup option. I can’t recall Hooper being used as a jumper by the Wallabies but even if he is a reasonable jumper his height precludes him from being a genuine jumping option in international rugby.

Selecting both Pocock and Hooper in the starting team would therefore require both locks and the number eight to be genuine jumping options.

Most people seem to believe Wycliff Palu is the Wallabies best, and many believe the only, choice at number eight. I am certainly of the view that he is by far and away the best option the Wallabies have in that position. However he’s a bulky man ideally suited to working well on the ground and whilst he’s used as lineout jumper he’s not what I call a genuine jumping option – he’s another backup option.

With a starting backrow of Pocock, Hooper and Palu that would therefore only leave the two locks as genuine jumping options. Only having two genuine jumping options would put the Wallabies at a significant disadvantage against top international teams and would require two exceptional lineout jumpers as your locks to try and compensate.

I think James Horwill, if fit, will be an automatic choice as one lock and he is a genuine jumping option. I think that Robbie Deans will choose between Sitaleki Timani and Kane Douglas for the other lock position with Horwill calling the lineouts. Yes, I know there are many other options out there that deserve to be considered but I think Deans has shown that his desire for the biggest bodies he can get into the pack will be the determining factor. Whilst I don’t agree with that philosophy, that’s what I think Deans is looking for.

Timani has not shown himself to be what I consider a genuine jumping option by international standards – he has the height but he doesn’t move quickly enough across the ground and he’s not dynamic getting into the air. The fact that of the 78 lineouts the Wallabies have thrown the ball to when he was on the field in 2012 only one was thrown to Timani tells us that the Wallabies also don’t see him as a genuine jumping option.

It’s not just that Timani is a big, heavy man (120 kg and 203 cms tall) – Douglas is heavier (122 kg) and nearly as tall (201 cms) according to the ARU website. But Douglas is a more dynamic jumper and I think can be considered a genuine jumping option.

If you think a starting backrow of Pocock, Hooper and Palu makes sense and you want Timani in the pack the Wallabies would only have one genuine jumping option in Horwill and three backup jumping options in Palu, Timani and Pocock. I think the Wallabies will have major lineout headaches with that scenario.

Unless Timani is developed by the Waratahs into a genuine jumper during the Super Rugby season his selection in the Wallabies starting side will be detrimental to the Wallabies lineout performance. Replace Timani with Douglas (or any other genuine jumping option) and you’ve still only got two genuine jumping options, which is not enough. So if you want the Wallabies to be able to compete in an area where the Lions will be very strong you’d have to replace Palu, Pococok or Hooper with a third genuine jumping option.

I’d keep Paul in the starting side rather than two open side flankers and play a number six who is a genuine jumping option. I expect that choice will come down to Dave Dennis, Scott Higginbotham or Hugh McMeniman who are all genuine jumpers.