When eight of our 12 first choice Wallaby test forwards have been struck down by injury the portents for an annus horribilis are surely mounting.

When eight of our 12 first choice Wallaby test forwards have been struck down by injury the portents for an annus horribilis are surely mounting.

And with a fair number of second tier past and potentional internationals also banged up it leaves our meagre playing resources looking a little threadbare.

But we can relax because the good news (if that’s what you can call it) is that in today’s professional era our opponents are essentially in the same boat.

With all this recent carnage the question arises: Are rugby injuries becoming more prevalent today than they used to be? The answer to that is a resounding yes.

Why is that? Off the top of my head I’d assume that compared to the amateur days professional rugby players are bigger, stronger and faster – ipso facto – the collisions are more severe than ever before and this would logically lead to more injuries.

Well yes, that’s certainly part of the overall story but there are a number of factors at play here that have led to the current situation. Rugby is a physical sport and the nature of the beast is that injuries will occur, full stop.

The incidence of injury per se can be reduced to some extent (more of that later) by various means but like death and taxes, there’s an inevitability about it.

One of the key factors responsible for the ever burgeoning injury rate is the increase in playing time – that is, the time the ball is in actual play, hence more opportunity for injury. This actually started in 1969 when the law was changed to preclude players from kicking directly into touch from anywhere on the field. You’d have lineout after lineout….

The IRB restricted the practice to kicking out from within your own 22, or for those that remember, the 25 yard line?

These days things have changed and stoppages are discouraged by: the phasing out of place kicks to restart a game; the introduction of free kicks for lesser offences (now short arms are di rigeur with generally a quick tap and go); quick lineout throws are now available; injured players are left for the trainer to sort out and a reduction in the number of scrums in the modern game. (Austin can tell you the latest scrum stats here)

But just don’t take my word for it. There have been a number of studies into rugby injuries both pre and post the introduction of the professional game. Also, there have been investigations into injury rates amongst club senior and junior ranks, and the results are more or less the same.

The best example is an Australian study1 into Wallaby player injuries from 1994 – 2000 (from the amateur to the professional era) and, although a bit dated, it’s the most revealing.

During this time the Wallabies played 73 Test matches and 13 non-Test matches. In addition, five Australia ‘A’ matches were played: 91 matches in total.

143 injuries were recorded during the 91 matches – 126 occurred during a game, and 17 during training.

One of their conclusions was that injuries essentially increase with the actual grade that’s being played – this applies at both senior and junior levels. The higher the quality, the higher the injury rate. It was noted in this report that injury rates in senior Scottish players doubled in the four years after the onset of professionalism.

In the two years of data collection before the game went professional (1994-1995), there was a Wallaby injury rate of 47 injuries per 1000 player hours. This increased to 74 injuries per 1000 player hours in the four years since then (1996-2000).

The most commonly injured player was the lock in the forwards and the number 10 in the backs, and the least injured player was the halfback.

At the international level, locks are no longer players whose only job is to win lineout ball. In today’s game they have a degree of mobility similar to a loose forward: they are important in scrummaging and at the breakdown where many collisions occur. It’s no surprise that they are often injured.

Forwards were disproportionately injured compared with backs. Again, this may simply reflect the fact that forwards are involved in more phases of the game than the backs.

In the backs the No 10 is generally the playmaker, receives the ball more often than most and is perhaps more vulnerable, especially with large backrowers running at him.

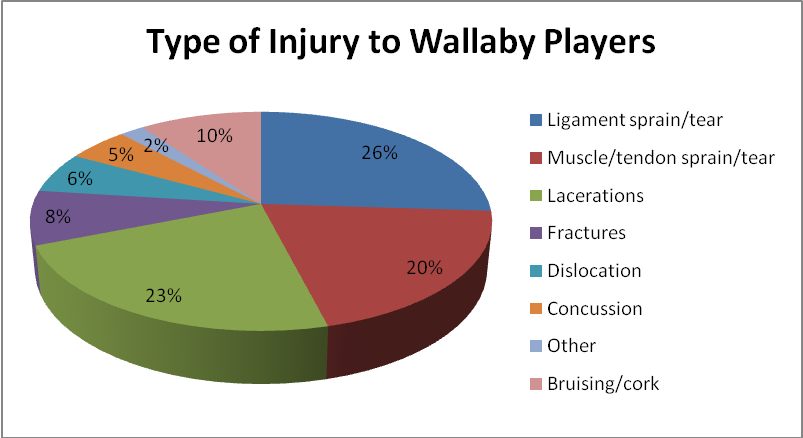

Most injuries recorded were soft tissue injuries, accounting for 55%. The most commonly injured site was the head, with 25.1% of total injuries. Most (75%) of these were lacerations requiring stitches.

In total, lower limb injuries accounted for just over half. Most of these were knee and thigh injuries. The rate of anterior cruciate ligament injury in rugby union is reportedly two to three times that of rugby league.

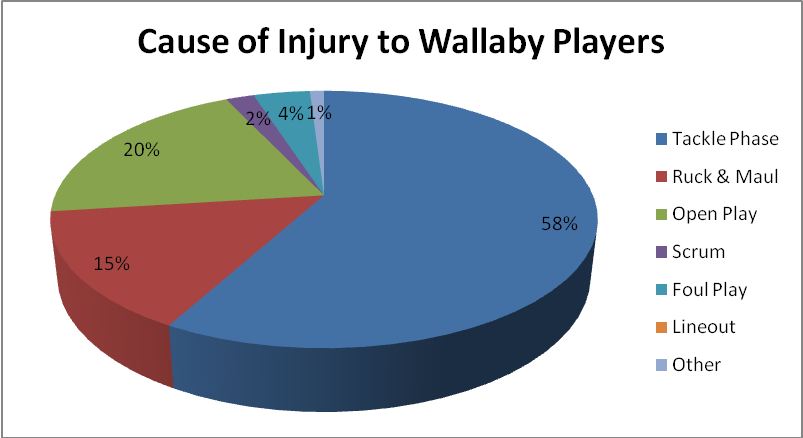

The phase of play responsible for most injuries was the tackle (58.7%), with both the tackler and the tackled player getting injured. Injuries were more likely to occur in the second half of the game, around the third quarter.

A New Zealand study2 backed up these results and provided data of a similar nature. This NZRFU study followed 704 players from all ranks of rugby during 2004. Some of the results were:

The higher injury rate in higher graded games was put down to –

- There is an increase in competitiveness as players move up the levels. If players are considered to have a certain capacity for dealing with the loads that are part of the game, then pushing closer to their limits increases the likelihood that they will receive an injury.

- Larger, more powerful players can generate more momentum and hence transfer greater energy to opponents in collisions that take place in tackles, rucks, mauls and scrums.

- At the higher levels of the sport the game is played at a faster pace, and the ball is in play for a greater proportion of the total match, hence there are more contact situations per match than at lower levels.

The rate of injuries for players aged over 16 increased over the three years leading up to the study.

Most rugby injuries occur in the contact phases of the game. Tackles and the breakdown (ruck and maul) carry a high risk of injury because they typically involve high energy collisions between players, and are reasonably dynamic.

There has been a large increase in the number of tackles and rucks occurring since the mid 1990s. It was suggested that this was a result of the ‘use it or lose it’ law around the maul, which meant that a tackler was less likely to attempt to remain on their feet following a tackle because of the risk of losing the ball if a maul formed and the ball carrier’s team did not make forward progress.

Foul play constituted 12% of the injuries recorded during the study.

Loose forwards were found to have the highest rate of injury, and outside backs the lowest. The loose forwards are typically the players who are most heavily involved in tackles and breakdowns in each match. These are the phases of play in which the greatest numbers of injuries occur.

For every 100 injuries a forward received, 36 were to the head and neck, against 23 for the backs. A greater percentage of injuries sustained by backs were to the lower limb (40%) than was the case for the forwards (31%).

Aside from the head – the knee, shoulder and ankle are the most commonly injured body parts. Concussion accounted for 8% of injuries to both forwards and backs, with fractures and dislocations making up another 9% for forwards and 10% for backs.

By far the most frequent injuries in rugby are sprains, strains and corks, which collectively accounted for 62% of injuries for forwards and 67% for backs. This pattern has been seen in most studies of rugby injury.

For players aged 16 and over, the rate of injuries was highest early in the season, dropped through the middle of the season, and increased slightly towards the end of the season. This pattern is not unusual and a number of reasons for this were suggested:

- Lack of experience – players are probably more likely to take up a new position at the start of the season or are new to the game.

- Lack of continued practice at the skills involved in the contact phases of the game – players do not usually practice tackling, scrummaging, rucking or mauling in the weeks leading up to the season.

- Lack of appropriate conditioning early in the season.

- Environmental conditions – harder grounds at the beginning of the season.

There is currently no evidence that wearing IRB approved shoulder pads reduces the incidence or severity of shoulder injuries. Likewise headgear with concussion related injuries.

The evidence indicates that injury rates are increasing for all participants of the game. That’s to do with both a transition to professional rugby (and the bigger, stronger, faster aspects of it) and likewise, in the amateur rugby system, the game is more dynamic than ever before and has adopted some of that professional ethos.

Conversely, injury prevention and rehabilitation services have profoundly improved since those dark ages.

What’s the answer then to our Wallaby conundrum? 1. Get used to it 2. Develop more depth.

Sources: 1. 2002 A Prospective Study of Injuries to Elite Australian Rugby Union Players – A Bathgate, J P Best, G Craig, M Jamieson 2. 2004 National Rugby Injury Surveillance Project – NZRFU