It’s good to be back, and this time we are in a position to apply some proper analytics to our game and see if rugby in Australia is indeed on the upward curve we all hope it to be.

I want to therefore introduce our readers to a few new analytical concepts we use at Rugbycology to better understand team performance. These will be used weekly in this new segment on Green and Gold Rugby, and I hope to convert you all into stats nerds over the next few weeks.

Spectacle ratings

In our context it’s never good enough to merely win or lose games, because union as a spectator sport is in constant battle with league and others for eyeballs. For union to progress, we need to offer a more entertaining product at elite level. But how do we measure if a game was good or average or poor?

While there are many other variables at play, we will over the course of this tournament focus on one particular metric: the amount of play events per minute.

Let’s quickly then compare our games this weekend to the Aotearoa competition across the ditch to better understand this metric:

It is clear that after 3 weeks, the kiwi games are ‘busier’ than the Australia games. For the same dollar amount, the Kiwis serve up a large chips, while the Ozzie’s currently only feed you a medium. Both competitions have a similar amount of set play’s, however in-between these ‘stoppages’, a lot more currently happens in NZ than here.

This is not the end of the world, provided that our team’s stay uber-competitive and that games are evenly matched. However we want our game to be as dynamic and entertaining as possible, and in this context we will be tracking the spectacle rating of each game for the remainder of the season.

Efficiency rating

Some teams play a flamboyant and dynamic brand of rugby. Others prefer a more pragmatic approach. Both styles are cool provided that it yields a good outcome on the scoreboard.

To allows us to track whether teams are ‘efficient’, regardless of the style of rugby they play, we use a simple efficiency rating that works like this:

On attack, an efficient team is able to move up-field, keep possession and score points. So the most efficient attack play is one that starts in your own 22 and ends in 7 points being scored. If however an attack starts in the opponent 22 and yields 3 points, it’s a lower efficiency play. Attacks that does not gain territory and where a teams ends up losing possession, will have a zero efficiency rating.

In defense, we add a value to a teams ability to prevent line-breaks and to regain possession within a reduced amount of phases. An efficient defensive play is this one where you do not lose territory, prevent points being scored against you,and win back the ball in under 3 phases.

With this definition understood, let’s see how the 4 Ozzie teams performed on attack and defense this week:

What? The Waratahs were the most efficient team of the weekend, yet lost their game? These ratings are crap!

Not entirely no. What this rating shows is that with possession, the Tahs were the most effective. The problem is that the Reds starved them of possession. The trick is to gain territory AND keep possession (conquer) in the same play. Otherwise it matters little how efficiently you attacked. The Tahs only managed to ‘conquer’ their opponent 22.8% of the time – the least of the 4 teams.

What the Blues will want to improve is their ball protection, because its now clear that these lads know what to do with the ball once they get it!

Over time, these efficiency ratings become more valuable and will help us understand which teams are making progress in attack and defence, despite the strength of their opponents.

Use of possession

Earlier in the piece I talked about how some teams choose an expansive approach and other a more pragmatic one. To measure which is which, we track 4 key metrics, and to illustrate this point I combine below our two winning teams, and then compare their average with the Crusaders season average. This gives us a nice benchmark to work with moving forward:

Handles per attack

Whether you kick, or carry directly, or pass the ball, teams who ‘let the ball do more work’, can be categorised as being more ‘dynamic’ or even flamboyant. The Crusaders handle the ball a bit more and over the past two games sported an attack efficiency rating of 32.9 compared to the Brumbies 31.1 and reds 32.2.

% Times kicked

It’s long been a fact that Kiwi sides kick more than all the rest. The Blues and Saders kick a good lot, but what sets the Crusaders apart is the variation of their kicks. Don’t worry mate, we will show you all the cool stats as the season unfolds.

3 pass sequences

Now this is the kind of metric that make us stats nerds forget the rusk in our tea. It is an extremely valuable metric because it shows the desire of a team’s attack and reflects on the skillset available to execute it in the face of a rushing defense. Secondly it helps us measure the line-speed of the defensive team. With a super-committed line-speed it’s often very hard for teams to string together 3 passes in a row.

In this regard the Kiwi teams (and the English national team) are way ahead of the curve. They are able to shift the point of contact and use more width, which all has an effect on how quickly the defense gets tired.

Tramline play’s

Imagine 15 players stretching arm to arm across a pitch. The gaps in between each player is much bigger than when the same 15 stretch over only two-thirds of the pitch. The same thing occurs when teams use the entire width of the pitch on attack. Not only are the fatties forced to run further to make tackles – the gaps in between defenders are also stretched. So look at that stat above again. This is the stark reality we are dealing with at the moment when comparing the Kiwi sides to ours.

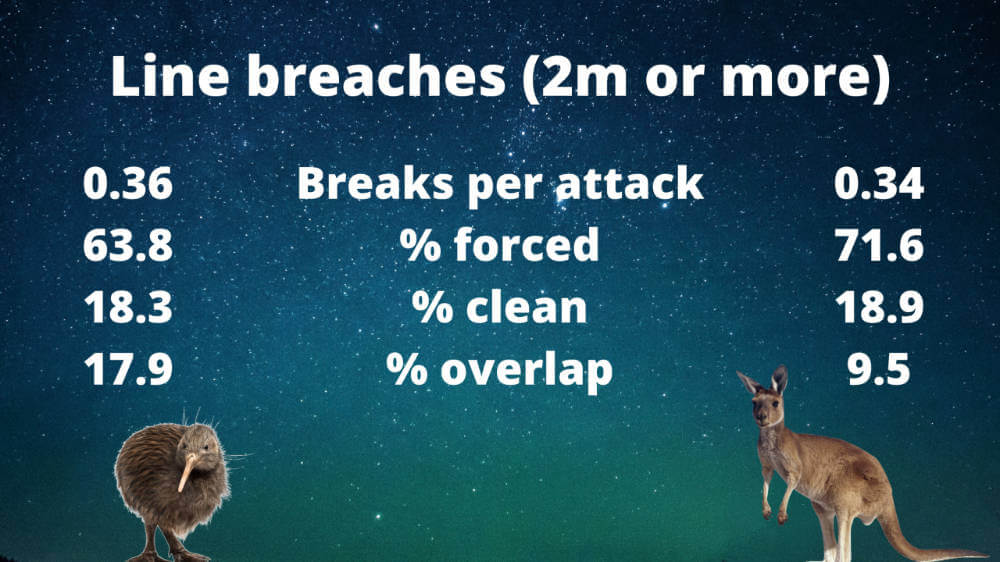

Let’s see below how this impacts a team’s ability to break the line and create gaps:

The good news for us is that our team’s are not that far behind when it comes to punching holes into the defence. In my opinion, strike running is probably the one area where Australia currently leads the world.

What we need to get better at is creating overlaps, and we can only do so if we develop a greater appetite for playing the footy all the way to the tramline. The thing about overlaps is that players make on average twice as many meters on an overlap as they do with clean breaks. Forced breaks in contrast rarely gain more than the minimum 2 meters required to qualify as a ‘break’.

In an era where we are truly blessed with great strike runners such as Paisami, Koroibete, Kuridrani etc, it is crucial that we sharpen our ability to get the ball to them more regularly.

Last thoughts.

I hope to update you guys on these efficiency metrics over the coming few weeks. We will also discuss our kicking game in more detail. Lastly we are studying the origin of tries to learn from which field zones and off which platforms Australian teams are more likely to score tries.

There is a lot to look forward to, and I hereby ask that you feel free to ask any questions you may have around these analytics on this platform or by engaging me on Twitter.