This was first published last year by our Prop Professor Nutta, but with the weekend scrum shenanigans of the Lions, it’s well worth another read:

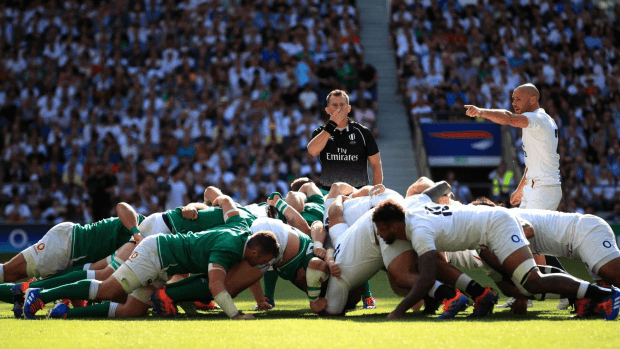

Hey Cobbers, KARL did a great referee’s assessment of the rugby scrum engagement sequence in his Wednesday spiel HERE. Read it if you haven’t already, I thoroughly recommend it.

In the comments section to his article, some thoughts were expressed by the readership about scrum collapses straight after the engage sequence, and particularly about props finishing up flat out on the ground – often termed ‘pancaking’ – and whose fault such events are. So, I started typing a response. But, given my response was rapidly becoming a brain-dump to rival War and Peace, I thought to reshape it into an article instead.

So here are some non-exhaustive, meandering thoughts on the matter of pancaking props – where one prop has gone face down, chest down, legs out and is flat, pancake flat, on the turf like some sort of perverse starfish.

Firstly, why listen to me? What makes me qualified to espouse? And that’s a fair question deserving an answer particularly given I wasn’t ever a Wallaby or a Waratah (so according to Matt Burke I have no right to comment at all). But I did start playing this game of ours as a tyke in the late 1970s before graduating to senior rugby (while still at school) in the late 1980s. And after some very forgettable minor representative stuff, a spell overseas and the odd premiership with a few proud clubs, I’m proud to say I’m still pullin’ on the boots and truckin’ about the paddocks. Although these days I’m doing so in the middle/lower grades of Sydney Suburban weekend warrior stuff, and allegedly in the odd country footy match by invitation or convenience (I deny everything). But yeh, by footy standards, I’m old and have been doing this front row thing for a while now.

Further, more than just being long in the tooth, I’m also big a believer in diversity, inclusion, and in broadening one’s horizons to make a person more holistic and balanced in their world views. In pursuit of that aspiration, I’ve played nearly all that time in jersey numbers 1, 2 or 3 just to prove it. I’ve diversified (“We got both kinds of music here: country and western”).

Thus, I’m a certified +45 year denizen of the front row and purveyor of dark arts across the breadth of all three positions therein. And I would say, leaving aside the levels of footy played at, the simple fact that I’m still an enthusiastic participant at the very sharp end of the approximately two-dozen scrum engagements per game, all involving the kinetic force of a Kingswood ute hitting a tree at about 50km/hr, means that by now, evidenced by still being upright, I know more than most about sorting scrummage shite from clay.

And for the record, to the inevitable juvenile twerps who invariably try to rile me onfield with hilarious originality focused on me being “Granddad” (because yeh, that’s a new one), well yeh mate I probably did shag your grandmother. Or was it your mum? Or both? But either way, I don’t remember them. Thus you probably best talk to that fella who pretends to be your dad about it and leave me be.

But to the matter at hand, based on what little I know, here’s an explanation of the basics surrounding a ‘pancaked prop’ that occurred at or straight after the engage sequence.

The first point to understand is that the pancaked prop is generally the tighthead – the guy who wears the no 3 (or 18) jersey and packs to the right of his hooker (no 2 or 16). It’s comparatively far less common for a loosehead (jersey no 1 or 17) to go full pancake for reasons to do with their body shape and the nature of the pressure as we will discuss later. And the tighthead usually gets to pancake via one of two routes: either the loosehead buckled in some manner (generally termed ‘hinging’), or because the tighthead himself dropped his bind and chewed grass. Let me explain…

Tighthead is the hardest scrummaging spot physically. It just is. Accept it. It’s conceptually the easier spot given its ‘square’ nature, but it’s far and away the more physically taxing. Mostly it’s hard because of two factors:

- Firstly, because a scrum packs ‘to the left’ and looseheads generally work more tightly with hookers, a tighthead (with his lock and semi-interested breakaway) is effectively taking on 5 opponents (opposition loose, hooker, lock, and semi-interested breakaway and no 8). It’s this imbalance on one side that makes the scrum naturally wheels clockwise. If we take out the nonces who rarely actually push (loosies), it’s still tighthead up front, plus his lock, against opposing loosehead plus hooker plus their lock (so it’s more often 2 against 3). Either way, it’s a lot of pressure being funneled through one guy’s shoulders, neck and noggin’ (sometimes up to 15,000 Newtons on the engagement by some credible studies).

- Secondly, because of the fact that the loosehead packs ‘left’ with no one outside of him, he is exactly that – a loosehead, because there’s no one outside him. That means the loosehead is naturally seeking an opponent and pressure to push against so he doesn’t fall over. All that pressure and weight must find an opposing force to hold it up. That invariably results in a loosehead naturally leaning to his right where there is pressure to contact. Thus, the loosehead is boring in and across the tighthead’s shoulder line by the sheer physical dynamics of the contest. This accentuates the clockwise wheeling motion. This means the tighthead’s opponent is not omni-directional and straight against him, but rather is multi-directional across all three planes of vertical, horizontal and depth as the opposing loosehead and hooker present differently and shift about. Generally, the loosehead will start further back, almost behind/under the Hookers armpit and his drive will angle in and up, while a hooker will be more forward and drive on different angles to strike or pressure the opposing strike. But the point is, it’s not a constant or stable front presented to the tighthead to contest against.

Put those factors of being both outnumbered and outweighed along with a physical dynamic that is shifting all over the place, and it makes for a highly challenging and fatiguing environment for the tighthead to contest, absorb and deflect the loosehead’s attack, hold steady and then inflict his scrums intent. That doesn’t mean it’s ‘easy’ to play loosehead, especially as having an ‘open’ side presents balance and pressure inequalities to be managed, especially on the engage. But loosehead is just not as physically demanding as tighthead.

So, as the ‘head of the spear’ on his right side of the scrum, to counter all that weight and the shifting dynamics of the duo directly against him and the piled-up force behind them, the tighthead will generally do three major things during the immediate engage event (plus a heap of other little things depending on the situation):

- Firstly, he must ‘win the engagement’. This means he must beat his opponent across the centre line of contact and be more extended out through the torso and the quads to achieve a stronger ‘body shape’ via which to combat the opposing pressure. For the tighthead to be ‘late’ on the engage is to then be stuck still somewhat hunched up from the pre-engage sequence, invariably higher than your opponents, and so in too weak of a body shape to withstand the pressures coming through from both the opponents and your own scrum behind you. The outcome of being ‘late’ is that the tighthead will be trapped both between and on top of all that pressure. This will usually make him ‘pop up’ (arse goes up while head stays down) and that means loss of control, shape and entering a world of stars, pins and needles and pain while your scrum disintegrates around you. As a tighthead, whatever else you may do, don’t be late.

- Secondly, at least initially, the tighthead must direct all his force ‘down and out through the chest’ so as to both keep his body shape strong and flat, especially through his right shoulder plane. He does this both to be an effective conduit for his own scrum’s power coming through him, and to counter the lifting pressure that will naturally come from the opposing loosehead who is trying to destabilise him, and thus not go up (see point prior).

- Thirdly, and related to the point above, the tighthead will endeavour to keep the ‘widow’s peak’ of his opposing loosehead’s neck balanced outside the point of his right shoulder. This is done so as to not give his opposing loosehead the opportunity to dive under his shoulder and so get access to his sternum (to push the tighthead up). And simultaneously, the tighthead will use his own over-the-top arm bind to trap and lever the opposing loosehead’s outside shoulder into a crunch. While technically illegal, this is done to stop the loosehead from ‘getting long’ down the tighthead’s outside/right flank, which would open the door to the loosehead being able to ‘walk around’ the tighthead, or worse still, “bore” and drive across the tighthead’s exposed ribs (note – this is why you often see a tighthead’s breakaway ‘slide up’ onto the opposing loosehead to stop this very thing).

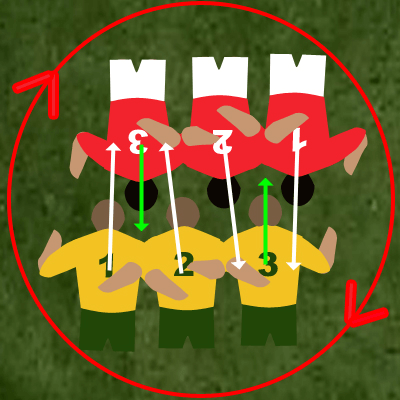

So basically, as seen in the pic above, the red tighthead has anticipated the ref’s call, so driven low, flat and fast and got over the gain line early. This allowed him to set his shape solid and ‘square’ before the loosehead could get under him and lever him up or pressure him through angles. A good and alert tighthead will try to do this for both your scrum feed and your opponent’s.

But by the tighthead pursuing this shape (as per pic), it can lead to what I call ‘early’ pancaking as the tighthead has perhaps over-anticipated the referee’s engage call and ‘gone early’ (or the loosehead deliberately arrived late). Either way, he arrives at the point of contact before the opposing loosehead, so by not having anything substantive to contact against, simply falls face-down flat. Alternatively, both props did arrive simultaneously, his opposing loosehead has engaged on the call, but by either weakness (or design or intent) has then ‘hinged’ and bent at the waist (as the blue prop is trying to do) to force the tighthead to collapse. Unless the tighthead is then quick enough to shorten his length and ‘chase his feet’, or strong enough to hold himself up through his bind, this then leaves nothing for the tighthead’s force to balance against. In that situation, without counter-balancing pressure, the tighthead cannot hope to hold his place with just his bind to lever his way out, so he releases his bind and ‘chews grass’, and so ‘pancakes’.

(notice the height of the blue tighthead’s backside).

All that said, sometimes the loosehead will pancake, but it’s rare. Generally it happens because the loosehead was trying to lengthen out his neck and spine under the tighthead, to get to the tighthead’s sternum area and leverage up, but either lost his footing or his bind, and so fell flat (from being overextended and unable to recover). Australian viewers may recall Scott Sio used to do this a bit, but again, it’s rare. More commonly, the loosehead will collapse with quite a noticeable left shoulder roll as his bind failed on the opposing tighthead and thus his outside/left shoulder rolled under him. This isn’t a pancake (because he isn’t ‘flat’). Rather he normally falls more on his outer/left side and this is, generally, a dead-set giveaway that he was trying to bore under and across the tighthead.

To explain a little further, tightheads and looseheads often collapse in different shapes because of the difference in how they formed up prior to the scrum. Because a tighthead operates more independently from the hooker/loosehead, he will shape up slightly in-front of the hooker to get over that crucial gain line more quickly. Secondly, because he is trying to establish a balanced and even plane of force, he will engage with his feet largely level with each other, or maybe only one boot length difference (the inside foot being marginally further back). As a result, the tighthead’s shape after engagement is quite square, flat and balanced. Thus, if/when he falls, he falls straight down flat, ie. pancakes.

Against that, the loosehead generally stands a little further back, often with his right shoulder almost under his hooker’s armpit, particularly on your own feed (so the hooker has an easier angle on the ball). And because the loosehead is leaning in with nothing outside his left shoulder, the loosehead’s inside/right foot will naturally be much further back than his outside/left foot which must be further forward to hold him up. As a result, the loosehead stands and engages with a much more split stance with left foot clearly more advanced than his right. This split stance is a great platform through which to then attack the tighthead, largely because by merely working off his left foot, the loosehead gets to attack across the tighthead rather than directly against him. But it also means that if/when a loosehead collapses, he either falls naturally in and under the front rows (painful and ugly) or he deliberately falls wider, but must roll his shoulder as he goes down.

In simple terms, without going down the rabbit-hole of the 10,000 other things that can influence a situation where 6 men are in direct contact over a silly shaped white ball while another 10 men attempt to influence that contact via indirect pressure, all in a situation where there is frequently +12,000 Newtons on impact and +8,000 Newtons of constant force thereafter being funneled unevenly across two intra- and inter-dynamic fronts, the core question for today concerning “what’s going on” and “whodunnit” when a prop pancakes in a scrum engagement comes down to who you believe as each prop accuses the other of shenanigans and dastardry:

- Did the red team’s tighthead prop anticipate the engage before the ref called (went early) and so pancaked because he had nothing to push against (blue penalty)?

- Or did the blue team’s loosehead not commit to the engage (hinged) and so left the tighthead with nothing to push against, manufacturing the tighthead’s pancake (red penalty)?

- Or did the blue loosehead commit, but could not keep his feet (red penalty)?

- Or did the red tighthead miss the engage and so bailed out by collapsing (blue penalty)?

- Or was the moment of engage so intense that the pressure forced one or the others bind to drop (whose penalty)?

- Or does the blue scrum suck so the blue loosehead suckered the ref to escape the scrum?

- Or does the blue scrum suck and so the red tighthead suckered the ref knowing the ref hates the blue scrum?

- Who shot JFK? I know, so why don’t you?

Good luck to you KARL as the Referee picking what’s happening among all that in real time. It’s a big ask. But don’t worry, old-man hard heads like me will be there to explain it to you as you get it wrong when you penalise me.

But in all that Dear Punter, just know one thing: that front rowers, real front rowers and not the fat backrowers looking to hide in a larger jersey, deeply love all this. We really do. We cherish it, study it, think about it, train it, and will talk about it all bloody day if you let us. And the proof of that is best found post-game in that true fronties will often be found drinking with their opponents rather than their own teammates. Why? Because scrummaging is a game within a game, experienced by few, loved by a fraction and understood by even less.

We are rare beasts. And that’s the way we like it.