Last weekend, Five English clubs qualified for the finals stages of the ECC (European Champions Cup). The other three quarter-finalists were French clubs, and it was the first time that a team from the Pro 12 competition (clubs or provinces from Ireland, Wales, Scotland and Italy) had failed to make the cut in the knockout stages.

While this achievement has been widely (and rightly) celebrated in the English media, it is underpinned by a more disturbing trend in the professional club game. The CEO of English Premiership Rugby, Mark McCafferty, has spoken previously of the pride he takes in the fact that the majority of players in the league are English-qualified (EQ):

“We have more than 70% of match-day squads qualified to play for England and we want to maintain this to ensure England is in great shape not only the 2015 Rugby World Cup but also for 2019 and beyond. The rise in the salary cap will help our clubs retain the best English players.”

The salary cap has risen to £5m per squad for the current year, plus allowance for two ‘marquee’ players or top internationals, who are excluded from the head count on the payroll. The reward from the RFU for maintaining the quota of English-qualified players has also risen from £240,000 p/a to £400,000.

So you would think that the squads that qualified for the latter stages of the ECC would exemplify the standard the McCafferty wants. In fact this is not the case among the six English teams in this year’s Champions Cup tournament:

- Bath Rugby – 70% EQ

- Exeter Chiefs – 63% EQ

- Leicester Tigers – 48% EQ

- Northampton Saints – 73% EQ

- Saracens – 55% EQ

- Wasps – 55% EQ

The three teams who qualified top of their groups (Wasps 4th seed, Leicester 2nd seed and Saracens top seed) for home quarter-finals all had the lowest quota of home-grown players – an average of 52%. The two teams who qualified for away quarter-finals (Exeter 5th seed and Northampton bottom seed) had an average of 68%, while only the team which was knocked out at the pool stage (Bath) achieved McCafferty’s 70% target percentage.

While the percentage of EQPs can be artificially boosted by including a handful of those who might realistically expect to play for England via the 3 year residency rule – Nathan Hughes at Wasps, Mitch Lees at Exeter, Mike Williams and Lachie McCaffrey at Leicester, Australian Kieron Longbottom at Saracens – or by grand-parentage (Brendon O’Connor at Leicester), the relationship remains pretty straightforward. The more Southern Hemisphere talent you recruit, the more immediate improvement you make.

So Wasps and Leicester have improved off the back of their recruitment of George Smith, Charles Piutau and Frank Halai (Wasps), and McCaffrey, O’Connor, Teuisa Veainu, Peter Betham and Mike Fitzgerald – with Jean de Villiers still to arrive – at Leicester.

Look at the big names who either have arrived, or will soon arrive in the English game: Ben Franks, Adam Jones, Jeremy Thrush, James Horwill, Victor Matfield, George Smith and Taulupe Faletau up front; Niko Matawalu, Jamie Roberts, Jean de Villiers, Piutau and Halai behind… and it is evident that the English Premiership is shifting far closer to the French model of success triggered by owners like Mourad Boudjellal and Jacky Lorenzetti in France: “Attract the best players that money can buy”, then put them all into a team of ‘galacticos’.”

While this movement is exciting from a club point-of-view, in the long term it only guarantees to widen the split that already exists in England and France between the club and international game. Clubs here are owned by private investors, who are increasing the power of their playing squads and the size of the facilities – Leicester’s stadium capacity has increased from 16,000 to 26,000 over the past 10 years. Their ultimate aim is to make the club product more attractive than its international counterpart, and they want to challenge the primacy of the international game.

The results in terms of the cohesion of game in England and France are worrying. Ex-Wallaby prop Ben Darwin via his excellent Gain-Line reports has outlined the dangers that face the national representative sides in both countries:

http://us9.campaign-archive1.com/?u=b1fe823fd17732155d02995c0&id=e6d649b723

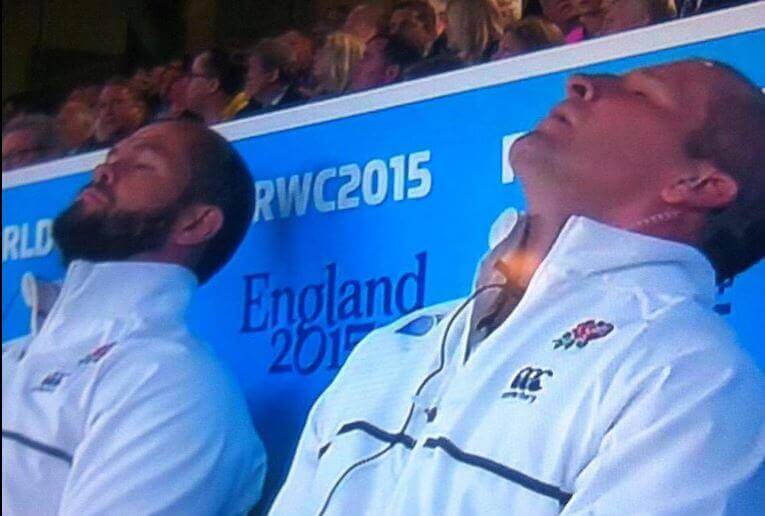

The five most ‘cohesive’ countries (with the best bond between international level and the professional level below it) are Ireland, Wales, Scotland, New Zealand and South Africa, with Australia and Argentina just behind them. All seven ‘achieved potential’ at the recent World Cup by reaching the knockout stages, while England and France (who are at the bottom of the cohesion table) did not. France were taken apart by New Zealand in the quarter-final, losing by 60 points, while England failed to even qualify for the knockout stage of their own tournament.

The irony of a situation where the country with the largest playing base cannot push that talent to the top of its own professional game will not be lost on the true England supporter. Sooner than it thinks, English rugby will reach a tipping point, and club momentum will put the entire future of the international game in jeopardy – just as it has done in Soccer.