In parts one and two of this article I’ve looked at some of the technical issues in scrums as a way of explaining some of the things we’ve seen in the scrums in this Wallabies and Lions test series.

Today, there are no secrets of the front row but I’ll look at the impact I expect from the new trial laws to be introduced next season and the how the angles work in the middle row to show why flankers are so important to props.

Whilst the article is less about the scrum in the third test the discussion on how important the flankers are to props is very relevant to the Wallabies scrum performance.

IMPACT OF NEW TRIAL SCRUM LAWS

There are three keys with the new scrum laws to be trialled next season:

- Props will be required to bind on their opposite prop after they have crouched into position and to maintain that bind during the engagement – the new call will be ‘Crouch, Bind, Set’;

- After the engagement the scrum will have to be steady with neither side pushing before the ball is allowed to be fed;

- The existing law that the ball be fed by the halfback in the middle of the tunnel will be enforced.

By requiring the props to pre-bind the front rows will have to start much closer. This will reduce the impact of the hit which is a safety initiative as studies have shown that most of the catastrophic injuries in scrums are caused by the hit.

THE LOOSEHEAD’S ANGLES WILL CHANGE

The other consequence of the pre-bind and the front rows starting much closer is that the loosehead prop will not be able to ‘dive’ under the tighthead as they do now. That manoeuvre is only possible because the loosehead starts far enough away to make the ‘dive’ and swing their arm up to make their bind once they’ve gone forward. This will change the loosehead’s horizontal angle.

The result of this will be less collapses caused by the loosehead missing their bind during this manoeuvre. As the loosehead won’t be able to ‘dive’ they won’t be able to get the back of their head across and under the tighthead’s sternum so the impact point will change to that shown in the image below. This will mean the loosehead is not engaging or driving on such an angle.

This will result in less scrum collapses and the loosehead’s vertical angle being much straighter – both positives as far as I’m concerned.

Unless they are a contortionist the loosehead will only be able to get their head under the tighthead, not their whole upper body as they try to do now. This will mean the loosehead will drive forward more and up less than they currently do.

This will benefit tightheads as it will remove the advantage looseheads currently have by being able to lift the tighthead up and destabilise them. I see that as another positive as the battle between looseheads and tightheads will be much more even. It will also make it harder for looseheads to wheel the scrum around in the natural clockwise direction as the tighthead will be able to stay lower and better resist the two v one force coming through at them.

THE HIT WILL NOT BE AS IMPORTANT

Whilst there will be a ‘small’ hit there will a pause after that whilst the packs stabilise and get steady before the referee allows the ball to be fed. This will allow time for the front rows to adjust their position and correct any errors in technique made during the hit.

Packs currently use the hit to drive the opposition pack backwards, feed the ball immediately and drive over the top of the ball. Effectively if a team loses the hit there is very little chance for them to compete in the scrum.

The hit will no longer be able to be used in that way as even if a pack is driven back by the ‘small’ hit they will still get a chance to stabilise themselves before the ball is allowed to be fed. The ‘small’ hit may still be a tool of intimidation to show the opposition how strong your pack is but the hit will not be the focus it is today.

ROLE OF THE HOOKER

Currently halfbacks feed the ball towards their own second row, if not into it. The laws haven’t changed requiring a feed in the middle of the tunnel but that law is not enforced and hasn’t been for some time. As a result, hookers quite often don’t even strike for the ball.

As the hooker for the team feeding the ball there is often no need to hook the ball back into your side of the scrum because the halfback has already done that for you. As the hooker for the team not feeding the ball there is little point in trying to strike for the ball to win a tighthead as it is physically impossible to reach your foot all the way into the opposition middle row and drag it back, particularly when the opposition pack is using the momentum of the hit to drive you backwards. As a result the hooker often isn’t used as a hooker and is instead used as a third prop helping to drive the scrum forward.

With the law requiring the ball to be fed in the middle of the tunnel to be enforced again, striking for the ball will once again become a very valuable skill. There are many hookers who are going to have to re-learn the skill and others who are going to have to learn it for the first time.

Good technique from hookers may allow your team to retain their own ball and even win the opposition’s ball. The scrum will once again become a contest of skill and technique rather than just brute force. I think that’s another great thing to come from the new scrum regime.

As hookers will be focussing on striking for the ball more they will not be as big a part of the drive forward. We will see less eight man shoves and more seven man shoves with the hooker only joining in the drive once they have either won or lost the hooking contest.

TECHNIQUE AND POWER RATHER THAN MOMENTUM

Under the current regime, where winning the hit is so important, props have to setup to engage as quickly as they can once the referee calls ‘Set’. As soon as the locks get into their setup position their weight starts to move the props forward so that they are almost tipping in to the scrum.

The props are primarily held back by the hooker’s right leg on the ground which acts like a ‘handbrake’ to stop the scrum moving forward and the number eight holding the locks back. The number eight initiates the forward movement of the scrum upon the ‘Set’ call by releasing the locks and pushing them forward. At the same time the hooker lifts their right foot to make a strike which releases the ‘handbrake’.

The force that starts from the number eight at the back of the scrum builds momentum when the forward drive of the four players in the middle row is added and increases again when combined with the drive of the props (and sometimes the hooker). The momentum generated from these combined forces drives the scrum forward and over the ball.

With the ball not allowed to be fed under the trial laws until the scrum is stationery there will be no momentum from the hit to start the drive forward. The pack will now have to generate the drive forward from a stationery position using technique and power rather than momentum.

Packs will have to generate this power through a co-ordinated drive as the ball is fed. Strong props will become even more important than they are today, however sheer grunt alone won’t be enough. A pack where all members have good technique that helps to generate and maintain power will have a massive advantage.

As I explained in part one of this article the only way force can be transferred all the way through the pack to the opposition is if the horizontal angle of the players generating the force is very close to the same angle and at the same height as you can see below from the All Blacks and the Wallabies where Ben Alexander also got into a good position.

As the hit will no longer have the influence it does today and there will be a pause after engagement allowing the front row to adjust their position, body shape / height at setup will be less important. However, the body shape / height of players before the drive is commenced and then maintaining that shape / height through the drive will be even more important than it is now.

If packs are pushing on different horizontal angles or any players don’t maintain a flat back through the drive, the power will be diminished.

THE IMPORTANCE OF FLANKERS TO PROPS

Power in a scrum is primarily achieved from the force generated by the middle row – the props add their power but their most important role is to transfer the force through to the opposition. Note that in this instance I talk about the middle row, not the second row or locks. That is by design because as I’ll show you there are actually four locks in the middle row, not two locks and two flankers.

Something often overlooked in scrums is that as the hooker is striking for the ball their foot is off the ground and they are unstable. If the locks behind them push on the hooker with their shoulders they will drive the hooker’s hips forward and they will not be able to get their leg into a position to strike for the ball.

To avoid disrupting the hooker locks can’t push with their inside shoulders and they direct all of their force through their outside shoulder on to the inside of the prop they’re packing behind.

This has been less relevant over the last few years as hookers have abandoned hooking for the ball but with the re-emergence of hookers striking for the ball it will again be a critical factor.

The laws of physics mean that, if for example you are the loosehead lock (on the left side of the scrum), you will direct all of your force through your left shoulder and that force will angle across the prop in a different direction to which they are driving, forcing their hips outward as shown below. There is physically no way that all of your force directed only through your left shoulder can generate force going straight forward.

To counter this each flanker has to push inwards on the prop. With the flanker’s force acting as a counterbalance the resulting force goes in the direction the prop is driving as shown below.

Each prop therefore effectively has two locks behind them and together they form a pod of three that is responsible for each side of the scrum. Whilst the whole pack still works together these individual pods of three are actually more important than how the ‘tight five’ work together.

If one side of the scrum is going backwards, it’s not just the prop who isn’t getting the job done – it’s all three members of the pod on that side.

Even though under the current law interpretations hookers don’t strike for the ball in every scrum, they still need to be in a position to strike if the opportunity arises so unless a team decides to implement an eight man shove, even today the locks shouldn’t disrupt the hooker by pushing on them.

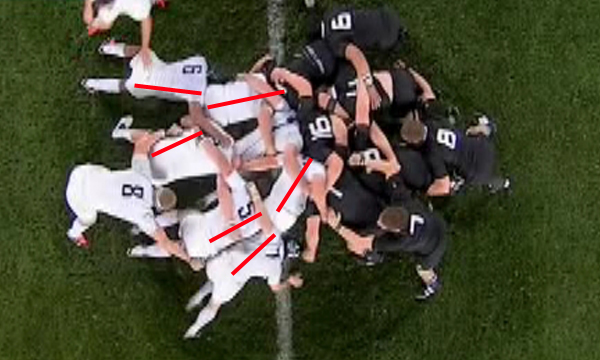

So, whilst I’m explaining the way the pods of three work in an article talking about the trial laws for next season, this is the way teams scrummage today. Here are some overhead shots showing you how the pods work independently and on different angles under the current law interpretations.

As you can see in those images as the scrum drives forward the props are often driving on different angles to each other and this means that the hips of the two second rowers normally split apart. Surprising as it may seem, the two second rowers do not actually work that closely together – they work more with the flanker in their pod.

As the hips of the second rowers split apart there is nothing left for the number eight to drive their shoulders on and their primary role becomes managing the ball or getting their head up to monitor the opposition attackers if they have won the ball.

However, the flankers must stay on the scrum – they are the vital counterbalance to each of the second rowers. Once they release their pressure driving in on the prop the power of that pod is reduced as the angle the second rower is pushing on is different to the prop he’s pushing on. You can see the angle of the Lions second rower and flanker behind Adam Jones in the second test in the image below.

So even under the current law interpretations the flankers are so important to props.

Once you understand the roles of the various players in the scrum it becomes obvious that the real drive in a scrum comes from six players, as the hooker is focussing on striking for the ball and the number eight has nothing to really drive on. Those six players form the two pods of three I talk about.

CONCLUSION

I think the trial laws are very positive for scrums, which will remain a vital part of the game. To scrummage well under these laws and interpretations forwards will have to improve their skill and techniques – scrums won’t just be about grunt and the hit, although powerful props will become even more valuable so power can be transferred through to the opposition.

What I’ve explained to you in these articles are not theories – they are techniques I coach and in my experience they work.

I hope that these articles have helped some of you to understand what’s happening on the field when a scrum is packed, whether it’s on television or at your local ground.